Wild Pigs Could Trigger Decimation of US Pork Industry

What happens when wild pigs are given 1,000 tons of groceries per day in the form of landfill trash? Expect an explosion in pig and litter size, and quite possibly, a $50 billion decimation of the entire U.S. pork industry.

The Savannah River Site (SRS) in South Carolina has become ground zero for research drawing a nexus between wild pigs and the potential introduction of African swine fever (ASF) into the U.S. At an SRS location, wild pigs have grown notably bigger and birthed larger litters in just a handful of years, attributable to the establishment of a landfill—a veritable hog buffet. The SRS landfill and other similar refuse dumps across the U.S. may be ticking time bombs, and could open America’s door to ASF, an epic porcine disease with no vaccine or cure, and a century-long track record of sweeping over international borders and wiping out billions of pigs.

Sooner or Later?

In the sandhills region of western South Carolina, roughly 25 miles east of Augusta, Ga., the Department of Energy's SRS covers a massive 198,046 acres across three counties (Aiken, Allendale, and Barnwell). The wild pig population of the general area has long been tracked by Jack Mayer, R&D manager at the Savannah River National Laboratory, and John Kilgo, research wildlife biologist for the U.S. Forest Service Southern Research Station.

In 2021, Mayer and Kilgo (along with Tommy Edwards and James Garabedian) published “Sanitary Waste Landfill Effects on an Invasive Wild Pig Population,” a report that turns anecdotal evidence into concrete fact. The report pulls back the curtain on an all-you-can-eat wild pig party, and the results are sobering, particularly when considering ASF ramifications.

In 1998, within an 8,000-acre wildlife management zone encompassed by the greater SRS region, Three Rivers Solid Waste Authority (TRSWA) began operation of an open (no fencing) 331-acre landfill encompassed by woods and shouldered in close proximity by two roads. The landfill’s actual garbage pits covered 69 acres and received 1,000 tons of waste each day—a magnet for wild pigs already capable of obtaining food from a litany of sources. A wild pig’s dietary latitude is phenomenal, from foraging roots, to accessing tree nuts, to hitting a freshly planted row of corn, to consuming the remains of dead mammals, or to functioning as a predator, i.e., the modus operandi of a truly opportunistic, efficient omnivore.

By at least 2001, wild pig sounders regularly were trafficking into the SRS landfill under cover of darkness and usually exiting close to dawn. By 2009, TRSWA employees reported 100-plus wild pigs foraging in the garbage pits every night. With plenty of cover and water in the surrounding wooded hills and hardwood bottoms, the wild pigs had maintained steady presence inside the area since the 1950s, but their numbers remained relatively stable. The landfill, however, upended the calculus.

In 2013, Kilgo began a telemetry study of mature sows with sounders in the vicinity of the landfill, utilizing trail cameras, trapping, and radio collars. His cameras positioned close to the TRSWA landfill told no lies: to the naked eye, the wild pigs appeared substantially larger when compared with pre-landfill photos and first-hand sightings. “John had pictures of pigs he was collaring and they were big, really big,” Mayer says. “I’ve been studying wildlife here since 1976 and I could tell instantly these pigs were bigger. Huge.”

“When I started trapping,” Kilgo concurs, “it was immediately obvious that pigs close to the landfill were noticeably bigger than pigs in the rest of the area. The telemetry showed them going to the landfill on a nightly basis. I imagine the jump in size began immediately after the landfill was first built.”

“It’s intuitive,” Mayer adds. “Let pigs into a landfill and they get free food, and they’ll increase in size, right? But no research had ever looked into exactly what else happens, and some of the answers we found should make people think hard about what could happen—sooner or later—in this country, and how devastating it could be for the pork industry.”

“In Front of Our Face”

Wild pigs have exploded in numbers across the U.S., possibly exceeding 6.5 million in just under 40 states, and their proliferation involves far more than a high birth rate and extreme intelligence. Wild pig control has become one of the greatest challenges in U.S. wildlife management history, and wild pig prosperity is partially due to a hog’s ability to thrive on a wide range of food sources—such as the fare offered in a landfill.

On control data ranging back to the 1970s, Mayer’s team already had a wealth of continuous SRS wild pig cull statistics in pocket. Across 11,296 hogs spread from 1980 to 2019, they found post-landfill weight gains in both sexes and all age classes. Comparing two lump sums from pre- and post-landfill wild pigs, weight gain averaged 20 lb. across all ages and both sexes (a shocking number considering the average includes piglets and juveniles). As a telltale exclamation point, the largest wild pigs ever killed at SRS were shot in woods within range of the landfill in 2018—a 400 lb. sow and 450 lb. boar.

“The research is striking in the pig size difference, especially in how fast this happened,” Kilgo notes. “There was one piglet we tagged at three weeks old and 8 lb. in weight, and we killed it a year and a half later at 250 lb.—an incredible rate of growth. All things being equal, he should have been about 130-140 lb., but most definitely not at 250.”

Further, with 799 sows harvested from 1980 to 2019, fetal litter in post-landfill sows registered at 7.1 piglets, compared with 5.9 for pre-landfill sows—just over one piglet in difference. The in utero litter increase of the single piglet meant a massive change in wild pig numbers. “The population modeling by increasing litter size as such over 10 years means a population difference of double in size—a huge difference,” Mayer explains. (He estimates close to 5,000 wild pigs currently inhabit the area.)

Following the thread, Mayer and Kilgo recorded a third category of significance directly related to wild pig size and frequency of travel in and out of the landfill: wild pig-motor vehicle collisions. According to data gathered since the mid-1970s, the SRS site had no recorded wild pig-motor vehicle collisions on either of the two roads (one private, one public) adjacent to the pre-landfill area, despite the constant presence of wild pigs in that area of SRS the entire time.

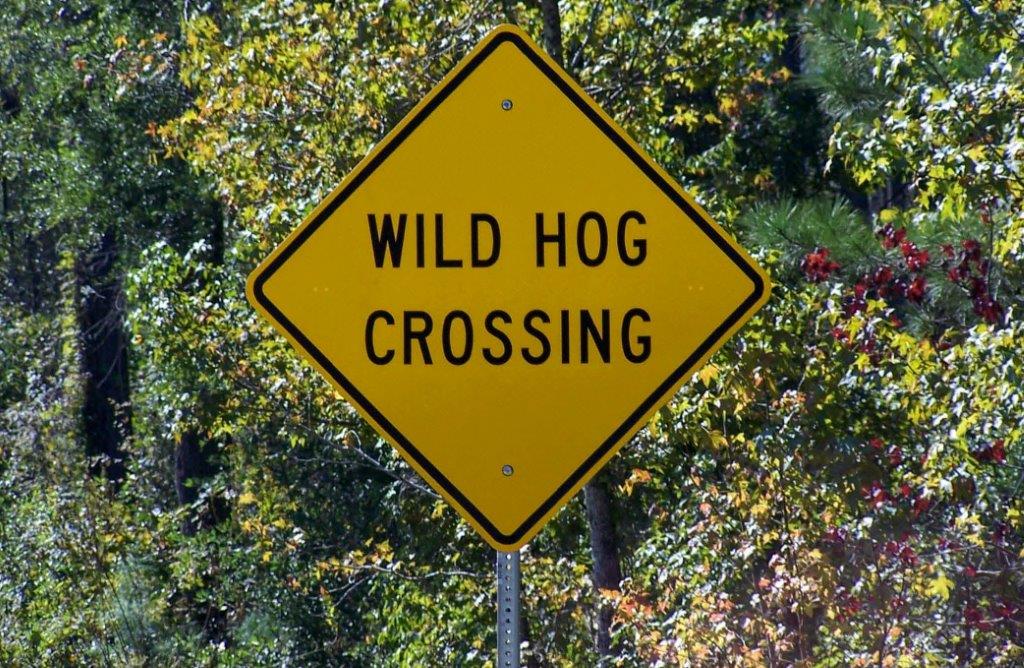

However, from 2000 onward, the same two roads experienced 20 wild pig-motor vehicle collisions, with at least 14 of the accidents occurring within an hour on either side of sunset or sunrise—the exact window wild pigs enter and exit the landfill for nightly foraging. “There were no collisions for a couple of decades, and then wild pig traffic shot up, and got so bad we had to put up the first ‘Hog Crossing’ signs in South Carolina,” Mayer says.

Considering the jump in size, fetal litter, and vehicle collisions, Mayer wasn’t surprised to see the wild pig population around the landfill possibly triple in size. “Control activities around the whole site are implemented uniformly by sending in subcontractors to kill wild pigs, but around the landfill, the harvest numbers tripled. We’ve never seen anything like this, and it means the landfill situation is producing bigger hogs, more hogs, and a safety risk. Allowing wild pigs access to a landfill is counter to controlling wild pigs.”

Yet, beyond wild pig control, the gravity of the Mayer-Kilgo research is noted in the report’s conclusion: “Several credible scenarios exist for the introduction of ASFV (African swine fever Virus) into the United States. Based on the paths of transmission across Eurasia, a number of these scenarios involve wild pigs foraging in landfills.”

Mayer offers a blunt, vernacular translation. “ASF could wreck the U.S. pork industry, and this is right in front of our face, and there are plenty of experts that believe ASF in the U.S. is just a matter of time. We know landfills played a role in ASF transmission in other parts of the world, and we know wild pigs are accessing landfills across the U.S. right now and could consume contaminated pork products. Look what just happened to China in 2019. They had about 440,000,000 pigs when ASF hit, the largest herd in the world, and had to kill at least 200,000,000.”

Game Over

ASF unleashes a sledgehammer effect on pig health, and triggered the death of a quarter (or more) of the world’s pig population over the last several years. The virus often carries a mortality rate close to 100% and is the kiss of death for a hog herd. If the virus reaches the U.S. pork industry, long-term losses are projected as high as $50 billion, according to a 2020 report partially funded by Iowa State University.

The report projects a strong possibility of ASF entry into the U.S. domestic pig herd through back door access: “The likelihood of the disease entering the U.S. through illegal entry of swine products and byproducts is high…”

“Illegal entry” of ASF into the U.S. is the precise scenario fostered by landfills and wild pigs, Mayer contends. “We’ve watched ASF spread like wildfire to the Middle East, Eurasia, Russia, Korea, China, and now into Western Europe. Landfills were a big component of ASF’s expansion in other parts of the world, and the same thing could happen here. We’ve never had an ASF outbreak in the U.S., and the last thing our pork industry wants is that economic devastation.”

Landfills, potentially the domain of heavy wild pig presence, are often the final destination for pork products illegally brought into the U.S., Mayer continues. “We get people from Asia coming into airports carrying pork products, and that pork gets confiscated by airport authorities. Everyone knows this has been going on, and still is. The confiscated pork gets thrown in the landfill, and all it takes is one sample infected with ASF to send the virus through a wild pig population, and eventually right into the domestic herd. We’ve got specially trained beagles in our airports (USDA’s Beagle Brigade) seeking out pork products—that’s how serious the situation is.”

The U.S. has at least 500 active landfills, most with no fences, and many within easy access of wild pigs. “Seminole County Landfill near Orlando, or Guadalupe Landfill beside San Jose, or landfills at Fort Rucker, Alabama, or so many other landfills; take your pick,” Mayer says. “I wish they would put fencing up, but that’s probably not likely due to the expense.”

“If you want to prevent ASF from having a greater likelihood of entering the U.S. pork industry, open access landfills are counter to that prevention,” Mayer adds. “We’re talking about high-stakes ASF consequence and the potential devastation for American pork. In many ways, ASF could be game over.”

For more stories from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com), see:

While America Slept, China Stole the Farm

Where's the Beef: Con Artist Turns Texas Cattle Industry Into $100M Playground

The Arrowhead whisperer: Stunning Indian Artifact Collection Found on Farmland

Fleecing the Farm: How a Fake Crop Fueled a Bizarre $25 Million Ag Scam

Truth, Lies, and Wild Pigs: Missouri Hunter Prosecuted on Presumption of Guilt?

US Farming Loses the King of Combines

Ghost in the House: A Forgotten American Farming Tragedy

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Misfit Tractors a Money Saver for Arkansas Farmer

Predator Tractor Unleashed on Farmland by Ag's True Maverick

Government Cameras Hidden on Private Property? Welcome to Open Fields

Farmland Detective Finds Youngest Civil War Soldier’s Grave?

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

Evil Grain: The Wild Tale of History’s Biggest Crop Insurance Scam

Grizzly Hell: USDA Worker Survives Epic Bear Attack

A Skeptical Farmer's Monster Message on Profitability

Farmer Refuses to Roll, Rips Lid Off IRS Behavior

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Shattered Taboo: Death of a Farm and Resurrection of a Farmer

Frozen Dinosaur: Farmer Finds Huge Alligator Snapping Turtle Under Ice

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows