Spaghetti Farming Hoax Ranks as Prank for the Ages

It was a farming hoax for history, masterfully executed as fake news by the media and ravenously swallowed by the public. But how in hellfire could the masses be fooled into believing spaghetti noodles grow on trees?

Wheat and water—the prime ingredients of pasta—are foreign to farming, at least in the eyes of many modern consumers, who often view agricultural activity as alchemy conducted in the frontiers beyond the suburbs. The ever-deepening gulf between field crop and grocery shelf has separated the public, arguably for the first time in human history, from its sources of sustenance.

The food-origin disconnect consistently manifests in whac-a-mole fashion, spewed by celebrities or bald-faced charlatans on social media’s information firehose, but nothing in the present digital age eclipses the jaw-dropping hammer blow dropped in mere minutes by the Great Spaghetti Tree hoax, a prank with few historical peers.

Rewind a handful of decades and cross the Atlantic pond to several minutes of madness on a fake farm. Sometimes, the past is present.

A Fitting Farce

In 1953, BBC television debuted Panorama, a news show precursor to 60 Minutes in the U.S. Panorama continues production to the present—the longest-running investigative journalism program on the planet.

Roughly 7 million homes in Great Britain had televisions in 1957, and viewers were limited to a channel choice of BBC or ITV. Panorama aired to an avid and loyal audience, sometimes drawing 3-4 million people every Monday. In 1957, April 1 dropped on a Monday.

Ten days prior to the April 1 broadcast, cameraman Charles de Jaeger sparked an April Fools’ moment of inspiration, purportedly via a seed planted years earlier by his elementary schoolmaster: “Boys, you're so stupid, you'd believe me if I told you that spaghetti grows on trees."

De Jaeger pitched producer David Wheeler with a spoof segment on spaghetti cultivation and noodle harvest, garnished by deadpan narration and film footage shot in purported pasta fields.

Although the bogus farming story was kept under wraps and shielded from the eyes of BBC brass, there was no massive scheme to delude the public. It was intended as a wink, a fitting farce for April Fools’ Day, and at a bare minimum, fodder to fill time on the episode.

Best laid plans.

Lock, Stock, and Bent Barrel

Given a green light and a whopping £100 budget ($120) by Panorama editor Michael Peacock, de Jaeger flew to the Ticino region of southern Switzerland to craft the film footage. But how to create a fake crop and film a nonexistent harvest?

De Jaeger bought 20 pounds of homemade pasta and hung noodles in laurel trees adjacent to his hotel in Castiglione on the shore of Lake Lugano. However, the spaghetti trees wouldn’t hold their crop, i.e., the wet strands slipped off the trees. Solution? De Jaeger placed uncooked noodles between moist cloth, an ideal balance for the perfect sticking consistency prior to insertion on tree branches.

With the means to a crop canopy established, he hired local women to dress in native Swiss costumes and filmed the “actors” picking noodles, placing the crop into wicker baskets, and spreading the pasta for a sun-drying effect. Following the harvest, he provided the ladies with a genuine spaghetti supper—filmed as if it was a time-honored, traditional ceremony.

Following de Jaeger’s efforts, Wheeler wrote the script—packed with outlandish agronomic detail. Richard Dimbleby, a highly respected anchor and former war correspondent with a classically authoritative delivery, added the voiceover narration. After a touch of floaty music was laced in the background, the package was ready for the public.

Lock, stock, and bent barrel, the Panorama team was pleased with the wry, but calm closing segment of its episode scheduled for 8 p.m., April 1, 1957.

Instead, all hell was about to break loose at BBC.

Hand to Mouth

Although considered television’s first benchmark April Fools’ joke, the Great Spaghetti Tree Hoax is grafted to a history of media-related food scams.

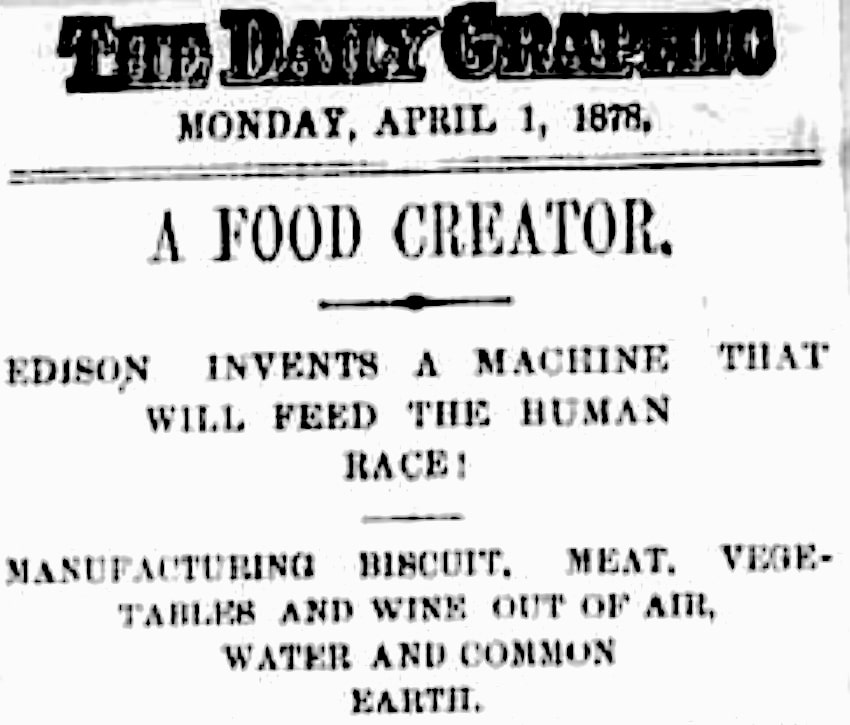

In 1878, Thomas Edison was climbing the ladder of achievement and fame. The miraculous phonograph was already on his resume, and he was on the cusp of delivering an incandescent light bulb to the world.

Playing off Edison’s notoriety, The New York Graphic newspaper published an outlandish piece in its April 1, 1878 edition, announcing Edison’s next invention: a food device capable of turning air, dirt, and water into meat, fruit, or wine. The Graphic boldly proclaimed, “A machine that will feed the human race!”

Newspapers across the country picked up the story and its fantastical details: “oranges and cabbages that have never felt the wind and rain, and pork and partridges that have never been alive.”

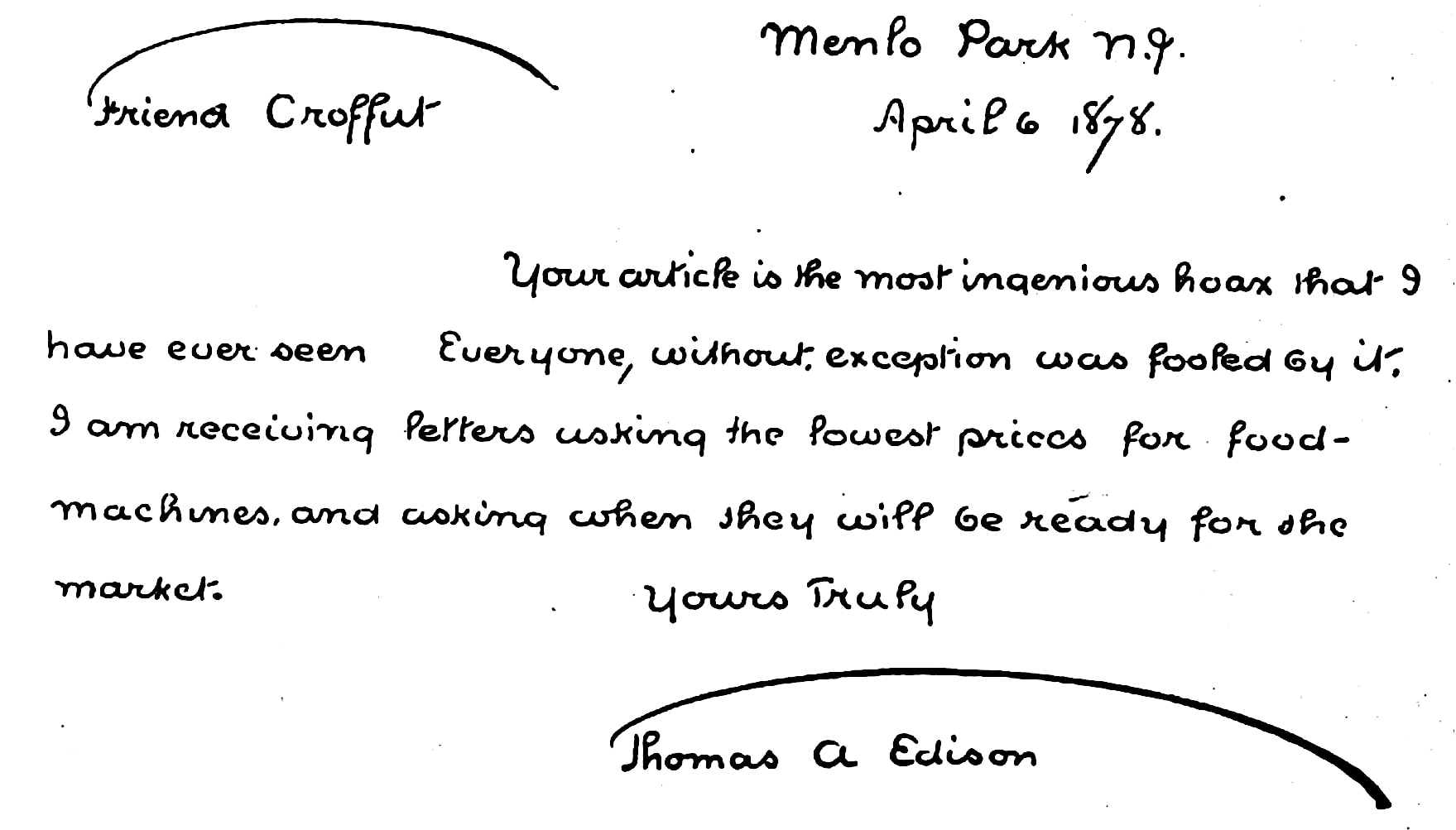

Edison, somewhat amused by the spectacle, responded with a tongue-in-cheek letter to the Graphic, “Your article is the most ingenious hoax that I have ever seen. Everyone, without exception was fooled by it. I am receiving letters asking the lowest prices for food machines and asking when they will be ready for market.”

Approximately a century prior to the false report of Edison’ food-machine invention, 4 million people lived in the United States, and according to the Census of 1790, 90% were farmers. In 1800, roughly 80% of America’s labor force was in the agriculture industry, and in the early 1800s, a typical farmer, according to USDA, grew enough food to sustain three to five people. In an age without gas-powered transport, refrigeration, or long-term storage options, most Americans were involved in some facet of agriculture. The basic demand of daily food access kept 90% (1% of U.S. citizens live on a farm today) of Americans living on the farm, hand-to-mouth with the realities of food sourcing.

By 1880, America’s farming ranks swelled to 23 million, but in tandem, overall population climbed to 50-plus million, exposing a widening gap between agriculture and the rest of the U.S. populace. In 1950, with agriculture in the process of mechanization and departure from mule power, the U.S was home to 150 million citizens, but farmer numbers dropped to 25 million, a slide that continues with 2 million U.S. farmers in 2022.

Conservatively stated, the seismic demographic change within agriculture spotlights the consumer’s separation from the most basic knowledge of food—a condition accidently exposed by transatlantic spaghetti noodles.

Too Late

At 8 p.m., April 1, 1957, Panorama jumped out of the gate with its typical news fare, reeling off multiple spotlights for its UK audience, culminating in a final caboose segment, introduced in studio by the august Richard Dimbleby, his voice coated in gravitas: “We end Panorama tonight with a special report from the Swiss Alps."

Seeing was believing.

Set to stringed elevator music, the farce began with rolling footage of a bumper, springtime spaghetti crop picked by women and placed into baskets hefted by men. Specifically, noodle strands hanging in laurel trees were presented as a bounty in the process of harvest. The premise was simple: Spaghetti grows in trees and is picked during harvest, in the same manner as apples, oranges, or olives.

Wheeler’s exaggerated narration outrageously invoked weather, agronomic angst, entomology, commodity markets, and plant breeding science—providing a layer of credibility for a gullible audience to swallow, despite the complete fantasy: “The past winter, one of the mildest in living memory, has had its effect in other ways as well. Most important of all, it's resulted in an exceptionally heavy spaghetti crop.”

“The last two weeks of March are an anxious time for the spaghetti farmer. There's always the chance of a late frost which, while not entirely ruining the crop, generally impairs the flavor and makes it difficult for him to obtain top prices in world markets.”

“Another reason why this may be a bumper year lies in the virtual disappearance of the spaghetti weevil, the tiny creature whose depredations have caused much concern in the past.”

“Many people are often puzzled by the fact that spaghetti is produced at such uniform length, but this is the result of many years of patient endeavor by plant breeders who've succeeded in producing the perfect spaghetti.”

After the story’s conclusion, Dimbleby reappeared on-screen and signed off for the evening, offering a telltale declaration for the April Fools’ viewers: “Now we say goodnight, on this first day of April."

Too late. The audience believed.

A “Splendid Idea”

Following Panorama’s spaghetti broadcast, BBC’s switchboard lit up with enthused callers asking for more information on spaghetti trees and pasta farming, many of them irate upon learning of the ruse. The volume of response forced the state-funded corporation to issue a clarification: “The BBC has received a mixed reaction to a spoof documentary broadcast this evening about spaghetti crops in Switzerland. The hoax Panorama program, narrated by distinguished broadcaster Richard Dimbleby, featured a family from Ticino in Switzerland carrying out their annual spaghetti harvest. It showed women carefully plucking strands of spaghetti from a tree and laying them in the sun to dry. But some viewers failed to see the funny side of the broadcast and criticized the BBC for airing the item on what is supposed to be a serious factual program. Others, however, were so intrigued they wanted to find out where they could purchase their very own spaghetti bush.”

Recalling the incident in 2004, Wheeler told BBC: “The following day there was quite a to-do because there were lots of people who went to work and said to their colleagues 'Did you see that extraordinary thing on Panorama? I never knew that about spaghetti.' They got laughed out of court and were very cross indeed that they had been taken in and made to look foolish.”

“We were criticized for doing it, but I had no regrets about it at all,” Wheeler continued. “I think it was a good idea for people to be aware they couldn't believe everything they saw on the television and that they ought to adopt a slightly critical attitude to it."

Even Sir Ian Jacob, BBC’s director-general, bought the feint. After the broadcast, Jacob scrambled for an encyclopedia and searched for spaghetti farming—only to find nada. "The spaghetti harvest was a splendid idea, beautifully shot and organized." Years later, Jacob wrote to De Jaeger. "This item has caused a great deal of delight, one way and another."

Smell-O-Vision

The Great Spaghetti Tree Hoax was a snow job, but the framework highlights the kneejerk response of a public often ready to place faith in whatever voice is heard last. The Delmarva Farmer once declared that Americans at large have entered an “Age of Agricultural Ignorance.” The Delmarva posit is debatable, but regardless of position taken, the stakes are high—particularly when an increasingly minuscule number of Americans engage in farming.

In an era where the average Joe or Jane consumer is bombarded with messaging on GMOs, pesticides, animal welfare, carbon emissions, and a litany of additional alarm bells, the propensity of the public to latch onto misnomers—minor or major—is a perpetual point of reckoning for the agriculture industry.

Final case in point: On April 1, 1964, only seven years after the Great Spaghetti Hoax, BBC pulled another sleight-of-hand trick, featuring a London University professor as guest, who claimed to be the inventor of Smell-O-Vision, a machine capable of transmitting smell via television signals. As the “inventor” brewed coffee and sliced an onion on set, he encouraged the television audience to stand approximately 6’ “from your set and sniff.”

According to The Times, many faithful viewers called BBC and confirmed the distinct odor of coffee and onions in their living rooms. Aye caramba.

To read more stories from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com — 662-592-1106), see:

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.

Bagging the Tomato King: The Insane Hunt for Agriculture’s Wildest Con Man

How a Texas Farmer Killed Agriculture’s Debt Dragon

While America Slept, China Stole the Farm

Bizarre Mystery of Mummified Coon Dog Solved After 40 Years

The Arrowhead whisperer: Stunning Indian Artifact Collection Found on Farmland

Where's the Beef: Con Artist Turns Texas Cattle Industry Into $100M Playground

Fleecing the Farm: How a Fake Crop Fueled a Bizarre $25 Million Ag Scam

Skeleton In the Walls: Mysterious Arkansas Farmhouse Hides Civil War History

US Farming Loses the King of Combines

Ghost in the House: A Forgotten American Farming Tragedy

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Misfit Tractors a Money Saver for Arkansas Farmer

Government Cameras Hidden on Private Property? Welcome to Open Fields

Farmland Detective Finds Youngest Civil War Soldier’s Grave?

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

Evil Grain: The Wild Tale of History’s Biggest Crop Insurance Scam

Grizzly Hell: USDA Worker Survives Epic Bear Attack

Farmer Refuses to Roll, Rips Lid Off IRS Behavior

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Shattered Taboo: Death of a Farm and Resurrection of a Farmer

Frozen Dinosaur: Farmer Finds Huge Alligator Snapping Turtle Under Ice

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows