The Cyber Worm has Turned on Soil Health

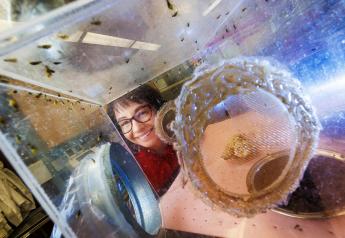

If you’re like Taryn Bauerle, an associate professor with the School of Integrative Plant Science Horticulture at Cornell University, you’ve spent a lot of time wondering what’s going on beneath the ground—and more specifically, that very small space where the root meets the soil. In that small zone, magic—some even call it chemistry—happens, and that chemistry has soil feedback loops with the microbiota living in the soil. Understanding this may help improve breeding efforts and soil management that improve yield.

To boldly plumb the depths of the soil and uncover these secrets, Bauerle knew she needed help. When you’re trying to solve a seemingly impossible challenge on earth, sometimes you have to look to a person with his eyes to the stars. So Bauerle turned to Cornell’s faculty list and reached out to Robert Shepherd, an associate professor with the Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering.

Although they both work at Cornell, they’d never met. Her pitch to Shepherd: Help her shine a light into the black box of plant and soil interactions.

Shepherd’s response? “I was all in, right away,” he says.

The first challenge: create a device that could move within a matrix you can’t see and is difficult to access. The second challenge: figure out how to capture data in an environment that’s not friendly to wireless transmission.

“There are physical limitations. There are energetic limitations, communication limitations. It's a really edge environment to be working in,” Shepherd says.

Even so, Shepherd was confident it was possible, and he looked to Mother Nature for inspiration.

“We know it will work because there are giant earthworms of the scale we're talking about that can move underground. And we have assistance from an auger, which will give us an advantage over even biology,” he says.

The project is supported by a $2 million National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to conduct the soil research and a $750,000 NSF National Robotics Initiative grant to develop the soil-monitoring robots.

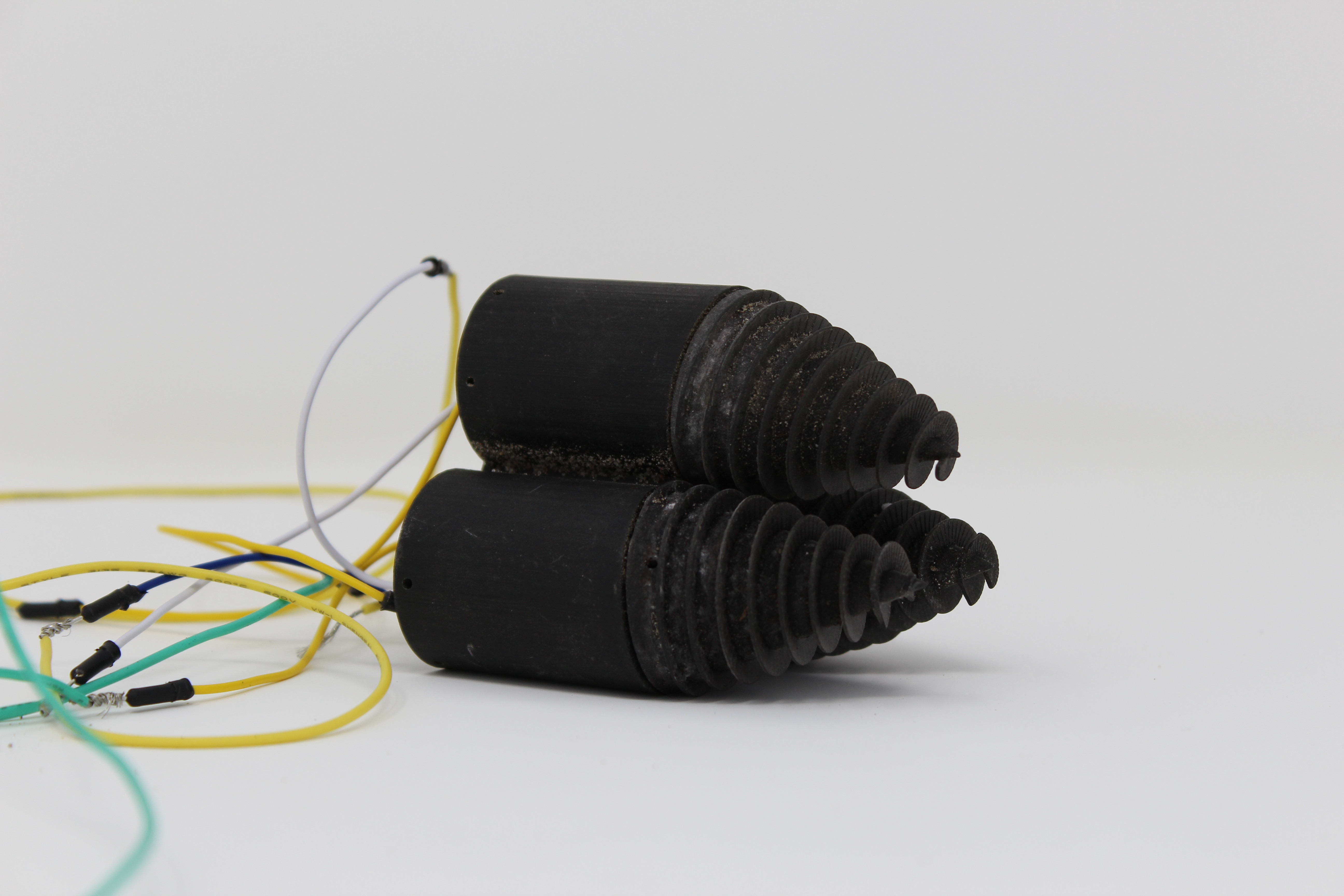

The plan is to develop 1’ to 2’ wormlike robots that both drill into the soil and can also mimic the peristaltic, or wave-like, movements worms make when they tunnel through the soil.

Initially, Bauerle expects the worms to cover small areas as little as a millimeter where the root meets the soil. Eventually she imagines the device could be used to traverse the length of a field, burrowing beneath a normal row of plants to gather data. One of the robot’s tests will be to travel an entire row of maize and collect data on soil density, compactness, temperature and humidity.

Sensors and testing may also include fiber optics to provide direct imaging of roots and reveal growth and angles. Fiber optics may also explore excitation and emission wavelengths of soil microorganisms and root chemistries, including carbon compounds exuded by plant roots.

Bauerle says there are many questions the robots may help answer—from how plants respond to changes in climate, including water availability, to how roots grow based on weather events such as droughts. Combining the in-ground data with information about above-ground characteristics may also help predict factors such as grain yield and stress tolerance.

“I think farmers have known for a long time the plant-soil interface is a very important one for growing crops and has a lot to do with plant productivity, and also with conservation and with soil properties,” Bauerle says. “Even though we've known that for so long, we haven't been able to access it. So, understanding that subterranean system in a much better way can help with a lot of future questions about irrigation, fertigation, soil health—there’s a whole basket of opportunities there.”

Shepherd’s lab has provided initial prototypes and expects to have a digging robot that can do basic measurements like humidity and temperature in under a year.

“As with most people who are working within this arena, all of us are trying our best to help farmers and help food security,” Bauerle says.