Damned By Data: State Destroys Farmer’s Yield, Pays $810,000 Damages

Fighting to save his farmland, Marvin Houin exposed government neglect with a damning paper trail. From 2009 to 2019, Houin watched his bushels crash and land value plummet due to bureaucratic dereliction. Ignoring a direct court order, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources swamped 407 crop acres, silted drain tile, destroyed yields, and placed all blame on Houin.

Risking financial ruin, Houin sued, backed by a roadmap of precision farm data and yield history. The precedent-setting result? Houin won a seismic $810,000 court judgement detailing DNR culpability.

“The government put our family through hell,” Houin says. “DNR tried to blame our farming practices and they tried to blame crop insurance, but we proved their actions as the source of our losses to the bushel. They couldn’t escape the data or the details.”

Sincerely. For the DNR, the devil was in the details.

Innocent Keystroke Error?

Thirty miles below South Bend, based in northcentral Indiana’s Marshall County, Houin farms 4,900 acres of corn, soybeans, and wheat, alongside his wife, Diane, and son, Charlie.

Four-hundred-and-seven acres of Houin’s operation border the west and south side of Marshall County’s Lake of the Woods, a public 416-acre body of water partially encircled by residential homes. Houin’s farmland drains into Lake of the Woods.

In 1986, to balance competing needs of agriculture and lake recreation, the Marshall County Circuit Court established a Lake Level Order dictating two average water levels controlled via a dam. From May 15 to September 15, the lake would stand at 803.85’ and from September 15 to May 15, the level would drop to 802.85. Adherence to the high-water mark of 803.85’ was vital: Any level above 803.85’ prevented adequate drainage from Houin’s field tile.

Following the 1986 Lake Level Order, water was adjusted on the two designated calendar dates, or as needed in the case of heavy rain events. Operation of the dam controls required on-site cooperation by Houin and a lake representative: two parties, two padlocks, and two keys.

However, in 2005, DNR took over dam operation. Several years later, in 2009, DNR posted a notice at the dam: Effective immediately it is the intent of the IDNR to leave the gate closed until the mandated opening date of September 15, 2009 unless the lake level elevation exceeds 804.35’. At 804.35’ the gate will be opened to draw down the lake level to 803.85’.

However, contrary to its public assertion, DNR did not use 804.35’ as the dam’s trigger level. Rather, IDNR used 804.65’—a drastic difference to farmland. The difference meant 1' 3.5” of additional water in Houin’s ditches and fields. For the next six years, DNR deployed its unofficial dam trigger policy resulting in an extra 1' 3.5” of water on Houin’s land.

(DNR declined to answer any Farm Journal questions related to the Houin case.)

Houin’s tile silted up, fields filled with water, and his crops suffered. “At one time, I measured 1.5’ across almost 500 acres,” he describes. “We couldn’t believe it was allowed to happen, but when we contacted DNR and showed them our farmland, they were totally apathetic. They weren’t snotty or arrogant—they just genuinely didn’t care.”

In 2015, following six years of Houin’s requests for relief, DNR announced a reduction in the dam’s trigger level to 804.35’, and blamed the past increase on a clerical mistake, describing it as an “innocent keystroke error.” Essentially, DNR claimed the 804.65’ water mark was a six-year typing accident.

“Innocent keystroke error? An extra 3.5” of water? They lied through their teeth,” Houin contends. “Government officials got caught in violation of their own regulations, and then covered for themselves. They wanted to turn our farmland into a wetland, and they almost did.”

Sympathy and Condolence

Despite Houin’s pleas, DNR did not consistently adhere to the Lake Level Order.

“It was transformative in the worst way for our operation,” he describes. “We switched some fields to soybeans from corn because instead of planting in April and May, we planted in June and July. Anyone who knows even a little about farming understands what a lack of drainage will do to a standing crop, or how it will wreck planting or harvest. It sometimes took 10 days for a field to dry after heavy rain, but DNR only opened the dam on their whim—not according to the Lake Level Order and not according to the law.”

Houin bled money. His 407 lakeside acres were expected to be valued at $8,000-$10,000, but with damaged drainage and silted tile, the land was worth $4,000-$5,000 per acre, he estimates.

Houin’s wife, Diane, describes the situation: “What do you do when the government ignores the very order that it created? We called, wrote, and visited every official at every level to tell them how our farmland was being strangled, but nobody would help. They smiled, nodded, and offered sympathy, but we never heard from them again. Thank goodness for Farm Bureau and Indiana Agricultural Law Foundation; they were tremendously helpful.”

Whether agency officials, state reps, national reps, or the governor’s office, the Houins received ample lip service, but no action. All the while, as the years rolled by, their farmland deteriorated.

“There was a gauge on the dam telling DNR officials when the lake needed to be lowered,” Houin recalls. “There was a running lake level on their own DNR website. There was my family showing DNR officials the damage in our fields. They knew exactly what was going on, but they chose to do nothing.”

Telltale

Facts, as John Adams once declared, are stubborn things. No less so on a farm.

Armed with a motherlode of data facts, the Houins had a choice: Go into court with limited finances to face government officials backed by unlimited resources, or kiss 400-plus acres adios?

Looking forward at more ruined cropland or backward at an extinguishing statute of limitations, the Houins sued DNR in 2017, represented by Janzen Schroeder Agricultural Law. “I can’t say enough good about Todd Janzen and Brianna Schroeder,” Houin notes. “We needed someone who would fight for us. That’s what we got.”

DNR’s apathy toward the Houins was noteworthy, according to Janzen: “DNR’s attitude to the Houins’ farmland situation seemed to be a ‘not our problem,’ policy. DNR appeared to believe they could run the dam however they wanted so long as the only people who got hurt were farmers.”

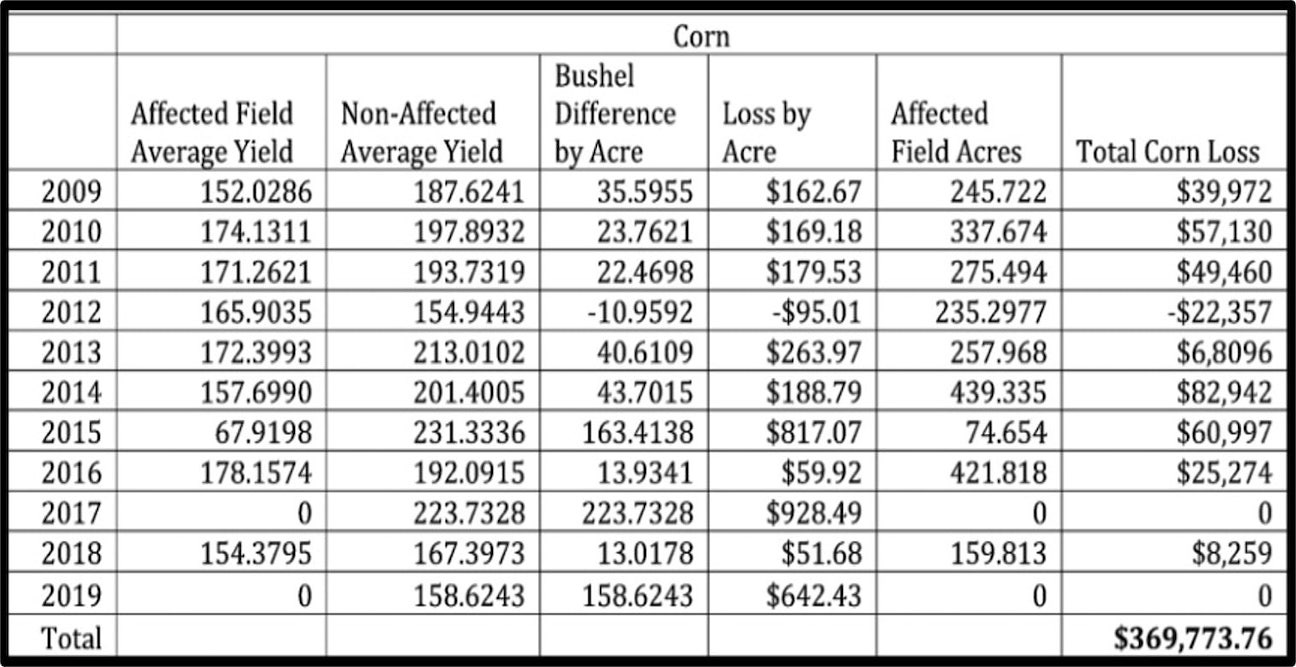

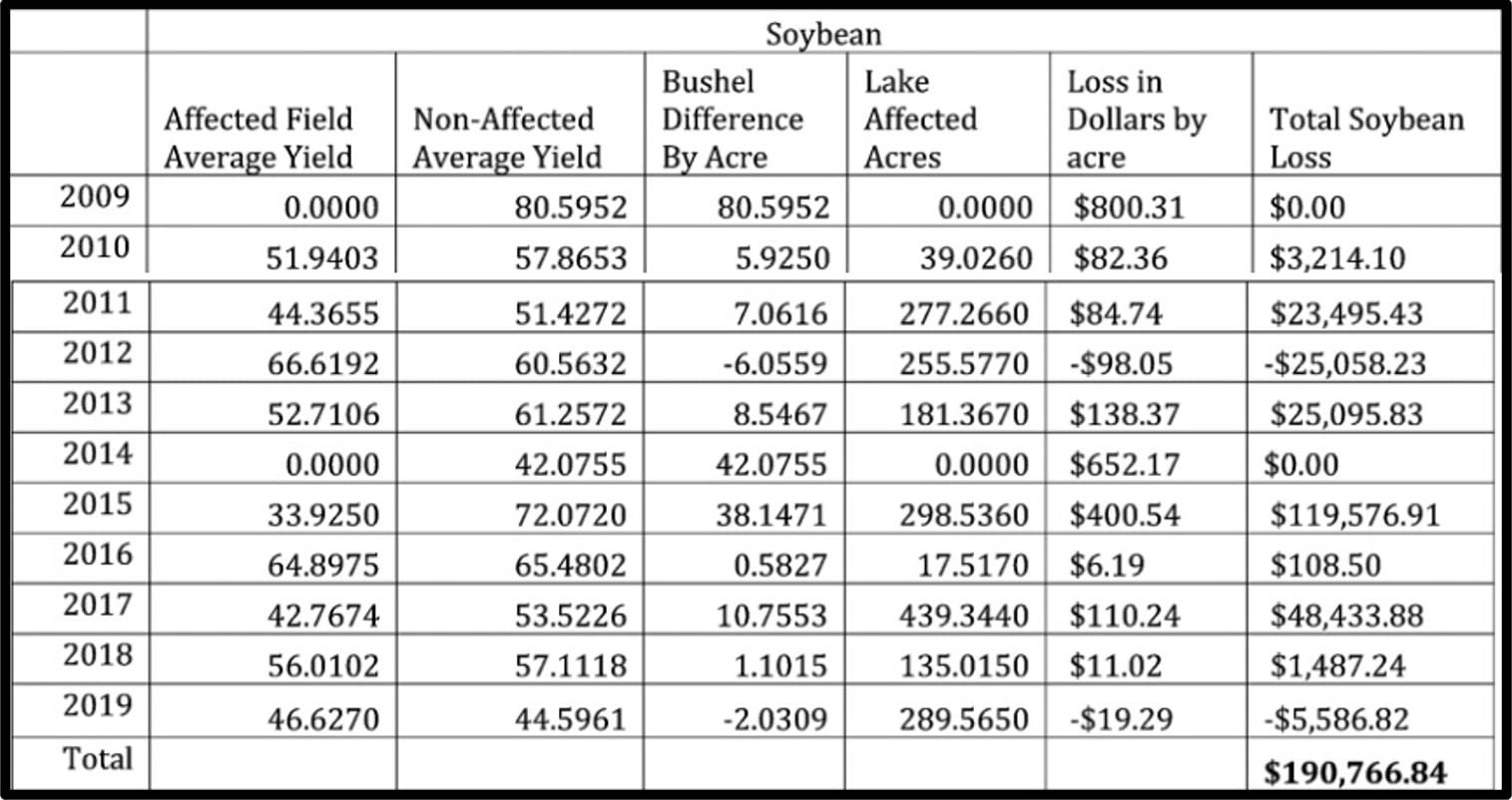

Janzen and Schroeder stuck to a straightforward, data-based strategy in Marshall County Circuit Court. They called on multiple agriculture expert witnesses to bolster the Houins’ agronomic contentions and illustrated the farmland disaster with straight lines between crop loss and lake level.

“The case was challenging if you looked at any one field in a given year, because you might be tricked by seeing only a 25% fluctuation in yield,” Janzen says. “It’s easy for DNR to say that a particular fluctuation could be a result of anything: weather, choices, or unknowns.”

“Instead, with modern data records, we showed the judge that you could trace the impact in every field to how the dam was being raised and lowered,” Janzen continues. “We did a comparison and showed fields nearby and other fields in the watershed that were planted with the same crops. We were definitively able to show: The difference was not weather, hybrids, or soil type. This was about drainage problems caused by operation of the dam.”

Laid out in court, the precision records were telltale.

Houin’s son, Charlie, presented field data at trial, detailing production pre- and post-flood. In a nutshell, Charlie provided numbers for each square foot of Houin acreage, and correlated soil type to damage. He also compared the affected acreage’s data to other Houin farms with the exact same soil types, planting periods, and varieties. Most vital, Charlie showed the corollary between farm data and lake level.

“We had a judge that wanted to see black-and-white data, and Charlie gave it to him,” Houin says. “The numbers were irrefutable and the last thing DNR wanted the judge to see. So DNR played the blame game.”

Snowflakes in Summer

DNR dropped blame squarely on the Houins with a trio of factors. First, DNR contended the Houin family was contributorily negligent by growing corn and soybeans on ground adversely affected by the lake level. “Outrageous logic,” Houin says. “They ruin our ground and blamed us for trying to use it. I thought I’d heard it all until I was told how to farm by a bunch of bureaucrats.”

Second, all Houin losses should have been subject to crop insurance claims, thus relieving DNR of all culpability.

“We tried so hard to explain to DNR that our other farmland elsewhere produced very well,” Diane says. “We tried to explain that the more losses you have, the less coverage you have. We tried to explain we had 200-bushel corn ground only producing a 70-bushel average over five years. Crop insurance gets worse as time goes on, but DNR’s position was all our affected acreage would be under perpetual crop insurance coverage. They understood nothing about farming.”

Third, DNR claimed its actions were excusable according to the common enemy doctrine: Every landowner has the legal right to change the flow of surface water, provided the flow isn’t dumped as a body onto a neighboring property. DNR claimed to be an ordinary landowner dealing with water issues, and by extension, the Houin fields were collateral damage of the common enemy doctrine.

In court, all three of DNR’s defense claims held up like snowflakes in summer.

“Flies in the Face of Common Sense”

In May 2021, Judge Curtis Palmer ruled in favor of the Houins—initially a $485,644 decision for damages to field tile, lost crops, attorneys’ fees, and post-judgement interest.

Palmer excoriated DNR’s behavior: The Court has found the DNR, by their conduct, assumed a duty to the Houins to regulate the operation of the dam in a reasonable manner, the DNR has breached that duty, and that breach has caused damages to the Houins. Those damages include damages due to lower crop yields and damages to field tile.

“When we heard the judge’s decision, it was like a load lifted off our backs,” Diane says. “Someone finally believed we were telling the truth.”

Palmer showed no tolerance for DNR’s defense claims, particularly its accusations that the Houins were negligent: The Houins had a right to believe the DNR would follow the 1986 Lake Level Order and had the DNR done so, the Houins’ fields would have drained appropriately and they would not have suffered damages. The Houins took affirmative steps by altering their planting, fertilizing and crop rotations to attempt to minimize the potential harm from extended periods of high water standing in the affected fields.

To adopt the DNR’s reasoning, to avoid being contributorily negligent the Houins should have planted zero crops in the affected fields and received a zero crop yield. While this approach may have maximized the Houins’ potential damages, it flies in the face of common sense and good farming practices. The Houins were not contributorily negligent, nor did they fail to mitigate their damages.

How did DNR officials react to Palmer’s ruling? After eight years of litigation; after a hefty sum of U.S. taxpayer funds spent; and after at least 13 state attorneys thrown at the Houins, DNR denied all responsibility and appealed. Time for another bite at the apple.

(DNR declined Farm Journal questions regarding taxpayer expense and the Houin case.)

Kicking and Screaming

“That was their real strategy,” Houin says. “Drag us through the courts and drain us financially. The facts, the law, our crops, and our farm meant nothing to DNR, but the process meant everything to them.”

The Court of Appeals reversed a portion of the Houins’ claims, but upheld the taking/damage factor. (DNR also appealed to Indiana’s Supreme Court, but was denied a hearing.) The merry-go-round madness spun back to lower court, where DNR requested a new trial.

“This was one of the most surreal cases in my career,” says attorney Briana Schroeder. “At every step, DNR made things as difficult, drawn out, and as expensive as possible. DNR had at least 13 lawyers—institutional litigators who worked for the state—who appeared against the Houins at one time or another.”

DNR officials, persistently seeking a path around precision data, attempted to drag the Houins through a new trial after the appeal process. “They wanted to start all over in court with a traditional real estate appraiser and have that person look for damage on the Houins’ farmland in 2023—not the repeated years of damage to crops and drainage tile,” Schroeder explains. “DNR fought tooth and nail because they knew this case would help establish precedent: If the government knowingly floods you—temporary or permanent—it has to pay for the damage.”

Facing the prospect of a judge lean on patience, DNR finally agreed to resolution far higher than the original $485,644 judgment. DNR agreed to pay the Houins $810,000. Case closed.

Unaccountable

After over a decade of wrangling with DNR, the true costs of the Houins’ fight were not financial.

Diane’s parents, Calvin and Marilyn Ralston, worked alongside the Houins when the DNR conflict began. (Marvin Houin and Calvin farmed together for 38 years.) Calvin, 89, died in 2016, a year prior to the lawsuit. Marilyn, 95, died in 2021, one month before Palmer’s decision in favor of the Houins. “My mother died in April, only weeks before the ruling in May,” Diane describes. “She never got to hear what happened. Ultimately, DNR did this to a dying, elderly lady.”

“Go back to 1986,” Diane emphasizes. “My parents went on good faith and believed the government would operate the dam according to the law. Instead, DNR forced three generations—my parents, ourselves, and our son—into the most frustrating and emotionally draining episode of our lives. It seems ironic that we won in court, but first had to watch our crops die, sell a farm, and get a new lender. Meanwhile, I never heard of anyone at DNR getting in trouble or being reprimanded for ruining our land. In fact, they got promoted. That’s government unaccountability and explains this whole story by itself.”

Benchmark

Houin vs. DNR proves preservation is paramount.

“What happens in this case without precision data? It’s possible the Houins might not have prevailed,” Janzen explains. “Over a decade’s worth of well-kept data unequivocally proved the Houins’ losses were attributable directly to the dam’s operation by DNR.”

“Keep your data,” Houin echoes. “Crop insurance, combine, yield maps, applications, GPS, and every other data set from your farming activity. Nothing is too small.”

The Houin family’s court victory is a benchmark for U.S. farmers and landowners: “DNR was terrified of our case because they knew if we won, our lawsuit would set precedent making the government liable for destroying farmland,” Houin concludes. “Guess what? Precedent just got set.”

For more from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com or 662-592-1106), see:

American Gothic: Farm Couple Nailed In Massive $9M Crop Insurance Fraud

Priceless Pistol Found After Decades Lost in Farmhouse Attic

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.