American Gothic: Farm Couple Nailed in Massive $9M Crop Insurance Fraud

Sex and power are primal, but greed is the father of farm crime. Welcome to a $9 million orgy of fraud steered by an unassuming husband and wife: American Gothic gone bad.

From the basement of a modest farmhouse, Robert and Viki Warren ran a crop insurance chop-shop: liquid eraser bottles, copy machines, telltale PVC pipes, and tens of thousands of forged documents. Across a six-year run, the couple’s purported crop losses were near-biblical, reaching critical mass when their stick-wielding farmhands destroyed a tomato field and tossed ice cubes and mothballs around the stalks—spurring the Warrens to brazenly claim yield loss due to a freak hailstorm.

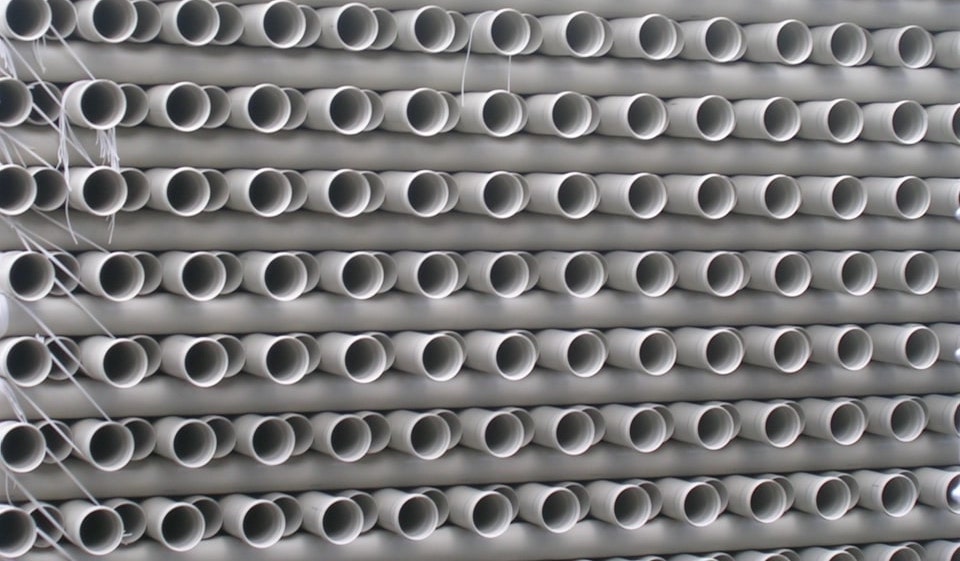

As USDA investigators and a bulldog prosecutor closed in on the scam, the Warrens hid a significant portion of their nouveau wealth, presumably burying caches of twenty-dollar bills stuffed inside plastic tubes. After serving a six-year sentence for crop insurance theft, Robert Warren began depositing peculiar stacks of moldy, pungent cash into a bulging bank account, all while assuring tellers, “Things are finally looking up.”

In reality, the curtain was crashing on the final act of an agriculture fraud for the ages.

Dark Art

In 1996, prior to becoming either the unluckiest farmers on the planet or serial liars, Robert Warren, 49, and Viki Warren, 43, were Buncombe County-based producers at R&V Warren Farms outside Candler, in western North Carolina.

The Warrens lived in a brick, ranch-style home fronted by a pickup truck in the driveway. No Cadillacs. No swimming pool. No shine. Modesty by appearance.

Their operation earned a reputation among buyers for crop quality and strong yields. They were among the most successful producer-packer tomato businesses in the eastern U.S., operating 10 farms in two states: North Carolina and South Carolina (later 26 farms in three states). Simply, the couple was very good at growing and selling tomatoes.

In 1997, the Warrens noted the frailties of crop insurance oversight. A mix of federal and private layers, crop insurance is difficult to parse for those outside the agriculture industry: Private companies, subsidized by federal dollars and USDA, sell insurance policies to U.S. farmers.

The Warrens understood the winding back alleys of crop insurance. However, they didn’t understand, or failed to recognize, federal investigators cold-nosing their paper trail, steered by lead prosecutor Richard Edwards.

Despite a career colored by criminals of every stripe—narcotics conspiracy, public office corruption, construction failure coverups, video poker kickbacks, and even an Army veteran pretending to be blind who took in disability payments while coaching archery—the Warren case stays fresh in Edward’s memory.

“Crop insurance fraud cases often involve farmers that are failures from the start, but not so with the Warrens,” he explains. “They had an excellent product in their fields. They just loved money.”

From 1997 to 2003, with help from several drive-by insurance adjusters, Robert and Viki raked in $9,280,000 million in fake claims (and filed for far more) and sold the hidden tomato yields out the back door. They mastered the dark art of the double-dip.

Good Times, Great Money

They cheated going in; they cheated going out. According to an indictment delivered by a grand jury in 2003, the Warrens began cooking the books after purchasing crop insurance in 1997. They lied about average yield history, inflated acreage, moved production numbers between insured farms, and grossly underreported total output.

From the get-go, they faked yield data and manipulated planting dates. In 1997, Robert Warren planted his Spartanburg, S.C. farm on April 15, the first day allowed by his policy—or so he told the E.L. Ross insurance company. In truth, he planted on April 4-12. He subsequently claimed cold weather damage for April-May and collected $157,712 in crop insurance.

Further, the Warrens reported remarkably minimal yields on several farms. On the Spartanburg farm, they claimed a harvest of 9,862 boxes of fresh tomatoes. The actual harvest was 78,670 boxes. They pocketed nearly $150,000.

Across all 10 farms in 1997, the Warrens claimed losses on five. Their numbers were fantasy: On their North Carolina farms alone, they professed a total harvest of 293,077 boxes, while really growing roughly 500,000 boxes.

All said, the Warrens received $644,467 in crop insurance or premium credits for their scheme in 1997, not even factoring in gravy from the double-dip.

At first blush, it was easy money. They ran the same scheme in 1998, dramatically lowered overall harvest numbers, fudged figures between fields, and pocketed a smooth $1,277,216.

Good times. Great money. But why not go big?

Mother of All Crop Fraud

Cast lots with us, we will all share the loot. My son, do not go along with them, do not set foot on their paths.—Proverbs 1:14-15

“The Warren Farms investigation is literally the mother of all crop fraud investigations,” said Gretchen Shappert, U.S. attorney for the western district of North Carolina, in a 2005 NPR interview. “It was a result of a perfect storm of individuals who were involved in fraud."

Enter George Kiser, Demetrio Jaimes, Harold Dean Cole, and Thomas Marsh.

George Kiser owned Kiser & Kiser Agency in Lebanon, Va. He sold the Warrens crop policies from Rain & Hail and E.L. Ross, and showed them the ropes of insurance fraud, advising the couple on how to receive payments for fictitious losses.

Demetrio Jaimes was a farm manager and supervisor who signed false documents and staged weather disasters. Harold Dean Cole forged spray records for the Warrens as a farm employee in charge of chemical applications. Thomas Marsh was a crop insurance claims adjuster who worked for Rain & Hail and E.L. Ross, and certified false acreage, damage claims, and false production figures.

“They were submitting reports to insurance companies from farms that would go in and out of existence by the year,” Edwards notes. “They fudged the serial numbers and kept it all unclear.”

By 1999, the Warrens had 20 farms. They churned out a blitz of forged documents: bills of lading, chemical receipts, sales figures, surveyor letters, acreage reports, planting dates, payroll records, invoices, manifests, and more. They claimed losses on 18 of the farms, with an abysmal overall average of 71 boxes per acre. Conversely, they reported a 3,386 box per acre average on the two successful farms. All told, they claimed 512,106 boxes in 1999, but their actual production number surpassed 1 million boxes. Their 1999 haul was $3.8 million off the backs of fellow farmers and U.S. taxpayers.

In 2000, steering a high of 26 farms, they doubled down with tomato and strawberry fraud, and conveniently suffered losses on 14 of 26 farms. Total insurance payout in 2000? $2,254,883.

Yet, the insurance lucre wasn’t enough. The Warrens wanted more. Specifically, they wanted $600,000 from a neighboring farm for alleged herbicide drift. Their greed was the beginning of the end.

A Haunting Detail

On Sept. 8, 2000, the Warrens sued Patten Seed. They accused an employee of Super Sod (an arm of Patten Seed) of spraying 2,4-D on a neighboring field with a highboy and causing drift damage on their tomatoes. Additionally, per their complaint, the Warrens alleged a sprayer hose broke on the highboy and leaked substantial amounts of 2,4-D on an adjoining backroad for three-quarters of a mile. In total, the Warrens pinpointed $600,000 in damages purportedly attributable to Patten Seed/Super Sod action.

During the exchange of information between the opposing legal teams, Warren Farms turned over sales and production data. Notably, the yield numbers were different from what the Warrens reported to E.L. Ross in 1999 crop losses. The figures given to Patten Seed listed overall 1999 North Carolina tomato yields at 865,997 boxes, yet the E.L. Ross 1999 North Carolina tomato yields were drastically lower—316,799 boxes. The discrepancy would haunt the Warrens.

Jumping the Shark

On Independence Day of 2001, the Warrens conducted one of the most outlandish dupes in the history of U.S. agriculture.

Covering their tracks, they switched insurance companies to Fireman’s Fund and added a new farm in Cocke County, Tennessee. Par for the course, the Warrens faked production records for the western Tennessee property, pretending to have grown tomatoes on the ground back to 1991—paving a full decade of forged documents with notarized lease agreements, false testimony from a realtor, fantasy planting dates, fantasy spraying records, bogus harvest records, false diagrams detailing a fantasy irrigation system, and hundreds of fake invoices.

Insurance acquired, the Warrens planted 252.2 acres of tomatoes on the Cocke County farm—so they reported. The real number? Roughly five planted acres.

On July 4, 2001, a devastating hailstorm materialized from a painted blue sky and released its fury exclusively within the bounds of the Warren’s tomato rows. Their farm employees used disposable cameras to record the catastrophe and submitted the hailstone photos as proof to bolster an insurance claim.

However, rather than a freakshow of nature, the hailstorm was a freakshow from the aisles of Piggly Wiggly or Walmart. Their farm employees purchased bags of ice and mothballs, flung the loads around the tomato plants, and snapped photos of the “hailstones” falling from the sky. A farmhand then walked the rows and obliterated the crop with a stick, with additional photos taken of the aftermath.

Bobby Chambers, farm manager at the Warren’s Tennessee operation, described the scene to NPR: "The way we did it, we was down taking pictures, out this row, and then we just stood behind it and throwed the ice over the top. To me, it looked like a hailstorm.”

"They had one Mexican who did all the beating, he beat every 16,000 of them,” Chambers added. “He'd just go through there and knock the leaves off of them. It made it look like where the hail had beat it up."

Over 20 years past the event, and after a career witnessing every shade of crime, prosecutor Richard Edwards is still jolted by the Warren’s moxie: “The plants were about 1’ high and completely destroyed. In the submission photos, sure enough, there was ice on top of black plastic and pitiful plants everywhere, torn apart.”

However, during later execution of search warrants, investigators gained access to all the photos on the camera roll—including the outtake pictures not turned in as part of the Warren’s claim. “There were two different sets of photos,” Edwards details. “In one set, in closeup photos the Warrens didn’t turn in, the hailstones were curiously cylindrical in shape, with odd dimples on both ends. Also, the path of the hailstones had miraculously fallen with heavy concentrations trailing from the bed of a pickup parked on the turnrow. It was a dry, dusty day, and no doubt the bag leaked and left a trail of ice cubes from truck to tomatoes.”

“In the second set of photos, the hailstones looked amazingly like mothballs—because they were mothballs,” Edwards continues. “Then they beat down the plants to shreds and took pictures from the front angle to make it appear as if the entire farm was damaged, but they’d only planted 6 acres of tomatoes and left the rest empty. We used satellite imagery with different color filters to prove they were lying. Yet, two adjusters, Don Farrow and George Kiser, both approved the claim.”

In the replant of the 252.5 acres, the Warrens pocketed $98,490. (They also declared freeze damage on five farms in the Carolinas for a tidy cleanup of $63,761.25.) All told in 2001, over 17 farms, they received $1,097,718 from Fireman’s Fund, and claimed they were owed an additional $3,805,610. The Warrens had jumped the shark: USDA investigators were closing.

Foot of the Cross

Staying on the move, the Warrens attempted to shift insurance companies again in 2002, seeking a switch from Fireman’s Fund to IGF. They used virgin farmer names—front producers—as window dressing to obtain lower coverage rates.

But on March 12, 2002, their plans went sideways when federal agents with search warrants descended on their home and two packing houses. Investigators found a trove of evidence in the basement of the Warren’s house—a veritable document production facility where paperwork had been manufactured for the duration of the crop fraud.

“We were able to see exactly how Robert and Viki created documents,” Edwards says. “They took bills of lading, chemical receipts, sales receipts, and much more, and did cut-and-paste jobs. Then they photocopied the new document and turned it in as proof of low yield or high yield or whatever they needed. Their basement that had been turned into a facility for cutting and pasting with old fashioned Wite-Out and Xerox machines.”

Due to the motherlode of falsified and forged paperwork, the Warren’s fraud became one of the most fact-intensive cases of Edward’s career. “We’re talking about nearly 1 million damning documents, as well as multiple farms and multiple submissions,” he says. “I was fortunate to have a group of four USDA agents and one IRS agent working on the case and they were fantastic.”

How convincing were the forgeries? “You could take the xeroxed documents the Warrens submitted and match them against the pink or yellow originals and spot the changes in figures,” Edwards notes. “You could hold the documents up to the light and see the Wite-Out or places where tape had been stuck on paper to hide changes in figures.”

Beyond the reams of paperwork, the Warren’s basement held a curious assortment of PVC pipes. Some of the pipes contained stacks of twenty-dollar bills wrapped in aluminum foil, then placed in cloth bags, and finally stuffed into the plastic tubes—impossible to locate via metal detector.

“We strongly suspected they were burying cash on their land, but there was no way to find it,” Edwards says.

Despite a mountain of evidence screaming out crop insurance fraud across a six-year shuffle, the Warrens denied all wrongdoing and professed complete innocence: They were victims.

“The Warrens were extremely defiant,” Edwards recalls. “They never came to the foot of the Cross until a gallows conversion. They finally pled guilty.”

Saddam Hussein of Crop Insurance

A year-and-a-half after the search warrants were executed, the grand jury dropped a stinging indictment in October 2003, layered with details of the con. According to DOJ, “The indictment charged the Warrens, as well as two of their employees, an insurance agent, and an insurance adjuster, with participating in an extensive scheme to defraud the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC) and several private insurance companies of more than $9 million between 1997 and 2001, and attempting to obtain an additional $2.8 million in 2001 through 2003.”

Year by year, claim by claim, and lie by lie, the investigation exposed the Warren’s fraud, connecting the dots to George Kiser, Demetrio Jaimes, Harold Dean Cole, and Thomas Marsh. The evidence was overwhelming:

—Filing fraudulent applications for crop insurance and then filing false loss claims;

—Submitting falsified production records, planting dates, and harvesting dates;

—Creating thousands of false, altered, and forged documents to support fraudulent insurance claims;

—Staging false weather disasters to substantiate false crop damage claims;

—Using false records to file a fraudulent civil suit against a neighboring farm;

—Attempting to create false farming entities that would appear to be run independently of Warren Farms, as well as creating false reports and forged documents in support of these attempts.

Significantly, the government used the Warrens’ herbicide drift lawsuit against Patten Seed/Super Sod to bolster its case. In May 2002, on the heels of undergoing federal search warrants of their properties, the Warrens curiously dismissed their suit against Patten Seed. Nonetheless, the raw yield numbers were inescapable, and Edwards pointed out an impossibility: “To make their court case look good against Super Sod, they submitted huge past tomato yield numbers, but on the same farms, they had submitted dreadful shortfalls to USDA for crop insurance claims. Therefore, it was time to pick a felony because they both couldn’t be true.”

Overwhelmed by a flood of evidence, the Warrens took a deal. Robert Warren pled guilty to conspiracy to defraud the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation (FCIC) and conspiracy to commit money laundering. Viki Warren pled guilty to conspiracy to defraud the FCIC and one count of mail fraud. The Warrens agreed to the forfeiture of $7.3 million, and $9.15 million in restitution to USDA.

Speaking to NPR, Robert Warren’s attorney, Sean Devereaux, deflected blame from his client: "It's fine for the government to issue sentencing memoranda and make Robert Warren appear to be the Saddam Hussein of crop insurance, but he's not. He basically was approached by people selling insurance and told, 'This is an easy thing to do. Don’t worry, this is the government's money, it's not the insurance company's money.'"

Almost the entire Warren crew confessed. Crop insurance agent George Kiser pled guilty and received a 27-month sentence and an $8.15 million penalty in restitution to USDA. Thomas Marsh, the loss adjuster, admitted guilt and was sentenced to 14 months and $767,000 in restitution. Harold Dean Cole refused to plead and went to trial. Cole was found guilty at trial of forging agricultural spray records on the Warren’s Tennessee farmland; his falsified records, ranging from 1991 to 2000, enabled the Warrens to triple guaranteed yield and increase the indemnity by $2 million. He was sentenced to 46 months and $2.18 million in restitution. Farm manager Demetrio Jaimes escaped with probation.

Viki Warren was sentenced to 66 months; Robert Warren was sentenced to 76 months. Roughly six years later, after he was released from prison on Nov. 29, 2010, Robert Warren quickstepped back to Buncombe County. Time to dig for PVC pipes?

Stale and Musty

On Feb. 22, 2011, while on probation at a halfway house in Asheville, N.C., Robert Warren opened an account at RBC Bank in Candler in the name of Beaverdam Valley Farms. Between April 13, 2011, and August 17, 2011, he deposited $208,463.40 into the Beaverdam account—in small bites never climbing above $9,000, ensuring no Currency Transaction Reports would catch the government’s eye. However, Warren was exposed by the odd physical condition of the money he deposited. Literally, the smell and feel of the bills set off alarm bells.

As reported by Eric Veater, IRS special agent: “The branch manager recalled that on two or three occasions she witnessed Robert Warren making the deposit of older twenty-dollar bills, specifically those without the security features added on the latest twenty-dollar bills, which were rubber-banded, wrapped in aluminum foil and ‘freezing cold.’ The branch manager recalled that Warren made comments such as ‘things are looking up’ and ‘things are getting better’ when he made the deposits. A teller at the RBC Bank Candler Branch said sometimes the cash that Robert Warren deposited at the bank smelled ‘stale and musty.’ The teller also said sometimes the rubber bands on the cash broke because they had lost their elasticity.”

Stale, musty, freezing cold, and aluminum-wrapped wads of money? “The currency that Robert Warren deposited fit with our speculation during the crop insurance case,” Edwards says. “We suspected that he dug that money up or retrieved it from somewhere, or both.”

Busted for bank fraud and probation violations, Robert Warren once again went back to the pen. Nine years after pleading guilty to crop insurance fraud, he was sentenced to 29 more months in prison.

What were the Warren’s plans had they not been caught? What drove their steadily rising and riskier levels of theft?

“They were buying property every year,” Edwards says. They were buying more farms. It’s purely conjecture on my part, and they didn’t have children, so I don’t know if they intended to sell the land as property values exploded. It seems to have all been tied back to generating more and more money.”

The Warren case is as old as time, Edwards concludes. “Love of money is the root of all evil. Maybe it’s just that simple. It appears the Warrens stole to steal.”

For more from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com or 662-592-1106), see:

While America Slept, China Stole the Farm

Priceless Pistol Found After Decades Lost in Farmhouse Attic

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.