USDA Scientists Testing New Cloud Seeding Technology

The dull drone of the engine buzzes the sky as a yellow air tractor sets its sights just below a cumulonimbus cloud puffing its cauliflower-shaped lungs toward the heavens. Mounted just off the wing’s trailing edges are rows of nozzles -- pistols ready to fire a positively charged mist of water into the sky. As the airplane feels the tug of the cloud’s updraft, the seeds of another Texas rain are sent charging through its core.

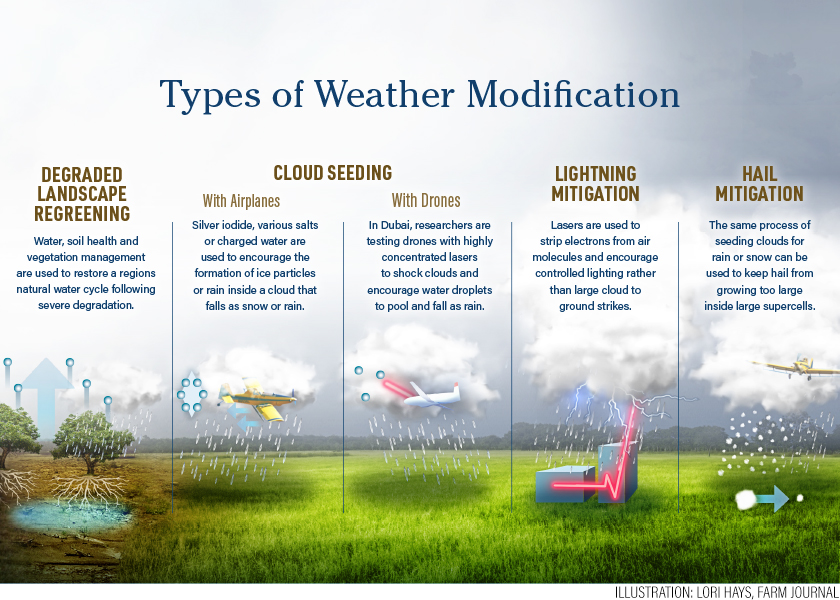

“If you introduce the right kind of particles into this supercooled area of the cloud, they can cause water droplets to freeze and additional ice crystals to form from excess water vapor in the cloud,” explains Andrew Detwiler, the president of the Weather Modification Association and a longtime university professor in North Dakota and South Dakota. “When you have a mixture of ice particles and cloud droplets, the liquid drops evaporate, and the ice particles grow becoming big enough to precipitate out.”

Science Not Fiction

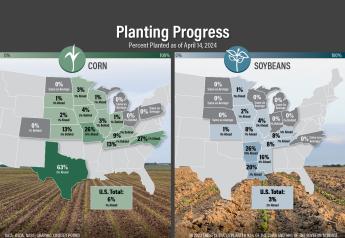

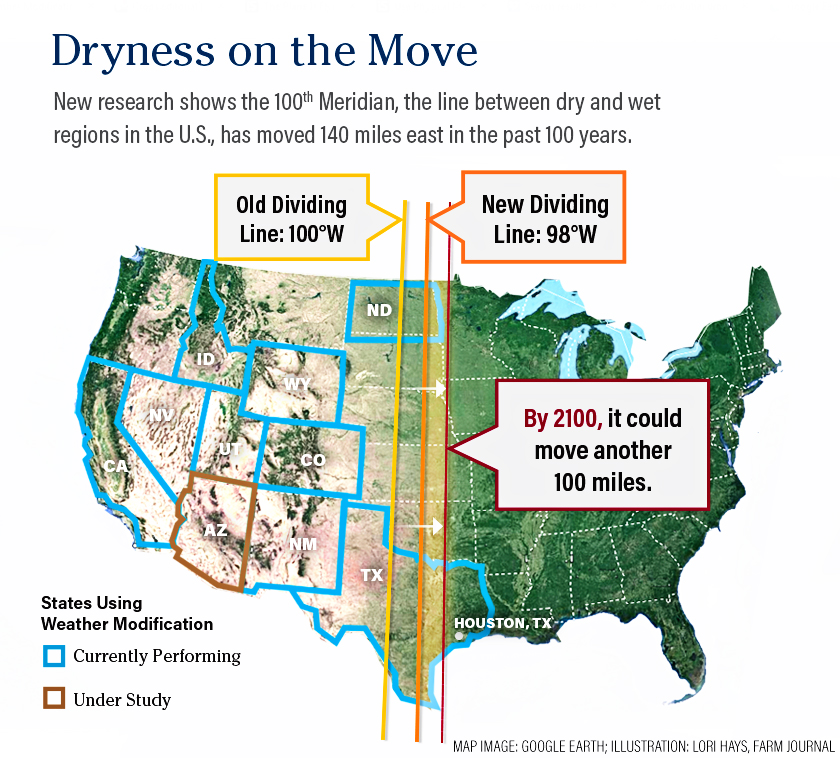

That is called cloud seeding and at least 11 states are already seeding or studying the possibility of seeding clouds in the western United States. The goal is to increase rainfall, add to reservoir storage or pile inches of snowpack into the mountains for spring runoff and recharge. For many cities and agricultural operations, especially out West, that stored water is vital to sustaining long-term viability.

The reality of weather modification has long been whisps of foggy science promising on-demand solutions while delivering statistical maybes or anecdotal actualities. First developed after World War II, cloud seeding has been attempted off and on for decades.

“Like many fields, weather modification took off with big hopes that you could have dramatic effects on precipitation,” Detwiler says. “The effect is known now to be much smaller than originally hoped.”

New Technology Takes Flight

While traditionally done with wing or rocket-mounted silver iodide flares, new technology is finding its way into the industry. In Dubai, scientists are trying lasers mounted to drones to coax excited water particles together ending with their fall from the sky. In west Texas, calcium chloride flares that work in lower relative humidity are getting a try.

“These particles are very hygroscopic and when you release them into a cloud, they attract moisture very quickly,” says Jonathan Jennings, meteorologist for the West Texas Weather Modification Association.

He’s also been working with Dr. Dan Martin, a research engineer with USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. Martin just patented a new technology using water.

“We're using tap water, but we're charging it as it exits the nozzle,” Martin says. “So, our expense on that set of materials is very little.”

“We're using tap water, but we're charging it as it exits the nozzle,” Martin says. “So, our expense on that set of materials is very little.”

Newly patented, the technology borrows from work a previous ARS scientist was developing to improve aerial targeting of pests. Through wind tunnel and controlled atmospheric testing, Martin found the charged water droplets also form ice crystals in clouds similar to traditional silver iodide particles.

"We did our initial testing in 2017 with 13 clouds," he says . "Those clouds were analyzed and the results showed we get a two to three times increase in some of the very major meteorological parameters."

Jennings and Detwiler say seeded clouds average between 5% to 15% more precipitation flux (how hard and how much it rains) compared to their non-seeded counterparts. In early trials, Martin’s positively charged water is beating that number.

“We're seeing about 25% to 30%,” he says. “That is from the initial data set, and we hope to at least confirm that this year.”

Once proven, that number could be significant and beyond the natural variability found in rain clouds.

“I feel like weather modification is on the brink of a mountain and we're so close to getting pushed to the top,” says Jennings.

At What Cost

Long-running droughts and new technology has communities in the U.S. and abroad giving cloud seeding another look. In 2008, it was widely reported that Olympic officials in Beijing used seeding to ensure clear skies ahead of the opening ceremonies.

“We have long-term statistical evidence from Idaho Power that cloud seeding has put more snow in the mountains,” says Eric Snodgrass, meteorologist with Nutrien.

How well it’s been able to mitigate drought, Snodgrass says, is still a question.

The challenge is in dry years, with fewer clouds, you have fewer clouds to seed. This is why Jennings sees weather modification as a long-term water management strategy. A tool to help bank and replenish supplies during wet years so it's available during years with less rain.

It’s also less expensive than other freshwater systems, such as desalination, reclamation and aquifer pumping. Jennings says their studies show 1 acre-foot of water seeded by traditional silver iodide flares costs less than $10 compared to desalination at $2,000 or more.

“Where the technology works best is where the clouds are least efficient,” Martin says. “If we can take an area that gets maybe 5” of rain a year and turn that into 10” a year, then you change the game. You can produce crops, where crops have not been able to be produced before.”

Question the Science

Since its inception in the 1940s, altering rainfall patterns via cloud seeding has been controversial. From questions about flooding to robbing moisture from other regions the ethics of messing with Mother Nature are much debated.

“One of the biggest questions we get is are you robbing Peter to pay Paul or making it rain here so it won’t rain downstream?” Jennings says. “What we're doing allows clouds to grow larger and lasts longer anywhere from a 15-min. extended lifetime in small clouds to upwards to 45 min. in larger clouds.”

“There's a budget to the moisture and if it's taken anywhere along the path, then what you're left with is your local recycled moisture,” Snodgrass says. “If you pull it from somewhere, it’s not somewhere else.”

Jennings says they aren’t taking rain from one place to give to another, they’re simply enticing the clouds to rain more when they do.

With more than 20 years of practice, he’s also adamant they aren’t making it hail. In fact, Martin’s new charged water project is in the process of being tested for hail suppression in North Dakota.

“Every year there’s $10 billion in property damage due to hail and $1 billion of that directly affects agriculture with the destruction of crops,” he says. “Our system converts the cloud moisture into rain and with less water available you get pea-sized hail rather than golf ball-sized hail.”

Charge the Future

Martin's charged water device was selected in 2021 as a top three finalist of USDA's ARSX2021 competition. The competition pits ARS teams against each other in a battle for transformative ideas in food and agriculture. The challenge awards three teams $100,000 to continue their research.

He's optimistic about the future of the technology, although, he admits buying and outfitting these types of planes won't be cheap. Those costs will one day be weighed against the cost of securing water in other ways.

"If you can provide more rainfall on arable land for crops, then hopefully, we can increase yield from that limited area we have available," Martin says.