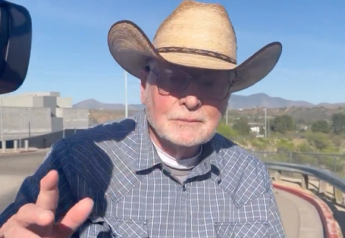

Skeptical Farmer Burns Ag’s Playbook, Steers Turnaround On 2,000 Acres

Roy Pfaltzgraff piled farming’s traditional playbook and recommendations on the turnrow and tossed a match on the heap. What remained beneath the ash? “Profit and a consistent way forward,” he says.

Skeptic, heretic, disruptor, eccentric—Pfaltzgraff pleads guilty to all. Double-cropping on 16” of annual precipitation, table sugar in-furrow, drastic synthetic fertilizer reductions, 14-18 crops per season, no specialized equipment, and direct-market scrambling, Pfaltzgraff has engineered a remarkable turnaround on 2,000 dryland acres.

He may be the most unconventional farmer in the United States. “What’s normal for me is way, way out for anyone else I know,” he says. “People think I’m crazy. They’re right, I am crazy, but I’m also the owner of a farm that is working great.”

Farming in the Armpit

On a mix of mild hills and flat ground (60% sand, 20% clay, and 20% loam), in northeast Colorado’s Phillips County (pop. 4,500), roughly 30 miles west and 30 miles south of the Cornhusker line, Roy Pfaltzgraff lll farms below the armpit of Nebraska. The terrain is typically bone dry and received less than 6” of moisture during the 2022 growing season. Mercury can dip to 25 F below in winter and sizzle upwards of 105 in summer. During growing season, temps can bounce from 45 at night to 100-plus at midday and 30-plus mph winds can blow without warning.

After a childhood spent on family farmland outside the tiny town of Haxtun, chasing the steps of his father and grandfather, Roy Jr., and August Krehmeyer, Pfaltzgraff returned to the farm out of college, but after a lost lease and drought he worked several jobs—the last in accounting. In fall 2016, Roy Jr., approaching 80, knees shot and a creaking back in full rebellion, approached his 40-year-old son with a blunt binary: “Come home or I rent out the farm.”

However, the proposition didn’t have ample meat on the bone. Year over year, Roy Jr. planted wheat, and a spring crop of corn, millet, or grain sorghum, yet scratched to break even. “If I come back, we have to make money,” Pfaltzgraff insisted. “Survival mode and ‘Live to farm another season,’ are out.”

Roy Jr. gave his full blessing. “I know how tough it is on the farm when someone says, ‘No,’ so I was not going to do that to my son. As long as he could show me a chance for profitability and a market, I got out of the way.”

With enough leeway to take the operation into uncharted waters, Pfaltzgraff returned home to farm and took the helm of day-to-day fieldwork. Roy Jr. implemented minimum till in the 1980s and no till in the late 1990s. His son, however, flipped the script. “We were letting fields go fallow one of every three years and following fertility recs based on old science,” Pfaltzgraff says. “No more; no way.”

Nitrogen, herbicide, traditional cover crops, fallow, and more—Pfaltzgraff began cutting off hallowed heads.

Two on Two

“Nutritionally, I need different foods as a human,” Pfaltzgraff says. “I treat my soil in the same manner and provide microorganisms with a diverse crop diet.”

Out of the gate in 2017, Pfaltzgraff added yellow field peas and brought back sunflowers. In 2018 and beyond, he exited fallow and entered continuous cropping (all crops drilled on 12” centers), adding black beans, buckwheat, black-eyed peas, clover, camelina, non-GMO corn, chickpeas, einkorn (an ancient wheat), flax, green field peas, milo, navy beans, oats, yellow peas, pinto beans, as well as beehives to boost the lot. (Sunflowers and buckwheat yields particularly benefit from honeybees; Pfaltzgraff is currently the only producer of buckwheat honey in Colorado.)

Many operations within Pfaltzgraff’s geography maintain organic matter at .5% to 1%, but Pfaltzgraff has boosted his soil to a 2.5% average in the top 12”, with several fields above 3%. “I started a highly diverse rotation based on Randy Anderson’s research that showed if you raise two crops seeded when soil is cool or decreasing in temperature and follow that with two crops planted when soil temps are warm or increasing, the pattern really screws with weed presence and can reduce herbicide use by 75%. Since I started the rotation, we’ve seen herbicide use drop by well over 50% across our operation—major savings.”

In 2018, Pfaltzgraff ramped up a revolving rotation door, but was perplexed by the extreme variations in soil health scores from field to field—even adjacent ground. In response, Roy Jr., created a data mine for each field with records dating back to 1985, tracing crop to year. Once the dots were connected, the code was cracked: “I said dad, ‘I know why you never made money. Every year, you only worked two-thirds of the farm and still had all the overhead.’ For example, the following wheat crop after fallow wasn’t making enough money to make the difference. As for the big differences in soil health it all came down to diversity, the more different crops on a field the better the score.”

A Living Root

Pfaltzgraff contends most innovations currently pushed by USDA revolve around cover crops, and he says the drumbeat is detrimental to many farms. “Around harvest, the general time to seed covers, is our hottest and driest time of the year and getting cover crops established was only successful in two or three out of five years.”

“U.S. agriculture has got to a point where guys beat their chests on soil health and declare how others should act like it’s a guarantee. Guys literally get up and preach to integrate livestock and cover crops to get more microbes and fungi. That kind of talk gets people in trouble and only comes from people who only know farming in their back yard, but are ignorant beyond. Let me put it real simple: You can’t do covers if it doesn’t rain.”

“For my ground, the answer to soil health is found in crop diversity. It’s sure not in organic production, because that’s way too hard on the soil and contains too much snake oil, in my opinion. You can’t do what I’ve done on my operation to get success, and I can’t copy you likewise, but we can learn individual lessons from each other. I do believe in a living root, but I don’t believe in cover crops as a religion.”

Pouring Sugar

Using a Haney test, Pfaltzgraff gauges nutrient generation from his soils. Generally, he reports a 70-80 lb. carryover of nitrogen each year. “I dropped the traditional soil tests. I’m a big believer that if you take care of soil microbes, they’ll convert organic matter into significant amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus.”

Recently, Pfaltzgraff raised 50-bu. corn. “Fifty bushels is a low number for most guys. Let me tell you some other numbers: 30 pounds of nitrogen and 7” of rain. That quickly changes the math. Generally, I use half the fertilizer of other guys. Even on wheat, I’ll go with 1 pound of nitrogen instead of 2 pounds to make a bushel. Healthy soil makes plants more efficient.”

“I don’t have an agronomy degree and I don’t pretend to know everything about farming and soil health, but I know how profit has changed dramatically on our operation. Again, I don’t copy anybody’s crop management, but I take bits and pieces from people I respect for their success.”

Russell Hedrick, Loran Steinlage, Ray Archuleta, Christine Jones, and Randy Anderson are cited by Pfaltzgraff as key influences in his mindset. “I go to CCTA’s No Till Conference every year and soak up lessons to tweak in my fields. I talk to guys in entirely different climates and then move particular details to my own fields.”

Since 2016, across his farmland, Pfaltzgraff has reduced herbicide and synthetic fertilizer use by well over 50%, he notes. “I’m not afraid to try something outta the box. Last year, we were having problems with Palmer in dry edible beans. We bought a Weed Zapper and hit the fields with 15,000 volts. Now maybe I’ll use sunflowers as a companion crop with the beans, and then kill the sunflowers at bloom to allow the beans to use them for shade and structure.”

Bottom line, Pfaltzgraff is willing to learn about anything that carries potential benefit—including table sugar. “Yes, I put old-school sugar in furrow. That’s not crazy at all and I’ll use it with any crop.”

“Over several years, I’ve seen a noticeable difference in grain yield, and this past year I’ve had test plots of half-pound up to 10 pounds in furrow. When I put sugar in the ground, the soil microbes see it and think there is a plant exudating sugar into the ground to feed them to uptake nutrients. When the seed germinates, it has triggered all this microbial activity and it therefore develops a larger root system to take advantage. If you think about what sugar is, it’s just carbon and water, food for the microbes and the crop.”

Despite 16” of moisture per year, double-cropping is also part of Pfaltzgraff’ crop regimen. He plants camelina in mid-November, expecting the first good snow to germinate the crop. Camelina is harvested in mid-June and followed with buckwheat, millet, or forage for a neighbor. “I never stop hunting for market opportunity and camelina is a great example. Next year, we’ll grow for a company turning it into renewable diesel fuel.”

Finding Demand

When Pfaltzgraff began growing a diverse roster, he heard the same echo from all quarters: No markets for out-of-the-mainstream crops. One of the first unique crops Pfaltzgraff grew was buckwheat. “I thought what everyone said was true, but I went looking for a market anyhow. I found a gluten-free malting company looking for buckwheat. I made a significant investment because I needed a different combine to ensure no cross-contamination. It has been good enough for us that we don’t have wheat this next year.”

The markets, he insists, are open to quick-footed producers. “I found out I had six bean companies within a couple hours of this farm. I started reaching out everywhere and now have a reputation. I regularly get contacted by companies as far away as Canada looking for specialty crops. One of them wanted 300 metric tons of buckwheat, but I can’t raise that in three years. There is huge demand if you learn how to look.” (After repeated calls from farmers seeking markets for stored crops, Pfaltzgraff and his wife, Barb, are developing a marketing class.)

Profit

When Pfaltzgraff hitched his wagon to continuous cropping, unique crops, specialty marketing, online sales, and weekly home deliveries, he began tapping consistent profit. He and his family operate as Pfaltzgraff Farms, LLC and sell direct to consumers with two brands: PFZ Farms and Brown Bag Birdseed.

“When I took over in 2016, we were at breakeven. Last year, we grossed three times what we made in 2016, even though our expenses are now twice the cost of what they were.”

After enduring a debilitating drought in 2022, Pfaltzgraff’s perspective is vastly different following six years behind the wheel. “Harvest was tough this year for everyone. I had neighbors that had zero harvest and kept their combines parked. But overall, we’re in good shape and we’ll be ready next year. By next April, we’ll have our equipment all paid for. We generally buy used and sometimes people think you need specialized equipment for unique crops, but not us: We have a sprayer, combine, tractor, and air seeder.”

Calling an Audible

What’s next for Pfaltzgraff? Rice in Colorado?

In 2022, Pfaltzgraff began testing 10 heirloom varieties of dryland rice. “I heard rice could be big in Colorado by 2050. Is that true? I don’t know, but why not get ready in case? Learn how to grow it in tiny quantities and find a market. Sometimes the future looks harebrained from far away.”

He also intends to convert 90’ of headland into pollinator strips on every field in his operation for his 25 beehives that tie into his living-root perspective. “I started raising field peas in 2017, and I started mixing it with Dutch white clover in 2019. The clover only gets 1’ tall, goes dormant when 45% shaded, and survives herbicide applications. I wanted to establish the clover as a perennial root, and I had it for 33 months until drought killed it this year. I’m still experimenting and hoping, but my bees absolutely love the clover.”

From Pfaltzgraff’s vantage point, his most important innovation, as always, will be crop rotation. Every rotation is planned one year in advance and is based on a mix-and-match approach. Sunflowers play a central role. “At a minimum, every piece of land gets sunflowers once every eight years. We use soil history and dad’s crop chart to place every crop, but the biggest piece of the puzzle is making sure two cool-seeded crops are followed by two warm-seeded crops.”

When 14-plus crops are at stake in a rotation, placement is often a muddled prospect, i.e., Pfaltzgraff sometimes calls an audible. “If we’re in a drought and we know field peas need moisture—we pull’em and find a better fit. Farmers always ask me, ‘How do you make your rotation?’ I joke that a dartboard is involved, but some years it seems that way.”

Small Bits and Pieces

Despite Pfaltzgraff’s innovative mind, there is nothing new in farming, he insists. His ideas are not original, just forgotten. “During the Second World War every farmer in Colorado was required to raise at least 20 acres of beans. There was a time when clover was normal and tilled into the soil for nitrogen. Sometimes knowledge gets lost and we have to go back and get it.”

The “regenerative agriculture or farming” moniker is often stamped on Pfaltzgraff, but in his operation’s case, he says the term needs adjustment. “What has happened on our operation since 2016 is more like ‘regenerative farmer,’ in the sense of myself and my dad. He is 80 and can’t wait for whatever we’re going to try the next season. I’m the same way, just itching to learn and try something that helps us maintain profit.”

“Anyone can do what we’ve done, but nobody can use our blueprint. I truly believe the land knows the farmer and if you make big, strange changes, the land fights you. But if you borrow small bits and pieces of other people’s ideas and treat your ground like the unique piece of farmland it is—unlike anyone else’s on the planet—that’s the road to success.”

“I’m an open book and there’s no tricks to anything I’ve done,” he adds. “Show up to my farm and I’ll let you see everything. No secrets.”

To read more stories from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com 662-592-1106) see:

Judas Goats: Agriculture’s Bizarre, Drug-Addicted Masters of Deceit Once Ruled the Killing Floor

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.

Bagging the Tomato King: The Insane Hunt for Agriculture’s Wildest Con Man

Young Farmer uses YouTube and Video Games to Buy $1.8M Land

While America Slept, China Stole the Farm

Bizarre Mystery of Mummified Coon Dog Solved After 40 Years

The Arrowhead whisperer: Stunning Indian Artifact Collection Found on Farmland

Fleecing the Farm: How a Fake Crop Fueled a Bizarre $25 Million Ag Scam

Skeleton In the Walls: Mysterious Arkansas Farmhouse Hides Civil War History

US Farming Loses the King of Combines

Ghost in the House: A Forgotten American Farming Tragedy

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Evil Grain: The Wild Tale of History’s Biggest Crop Insurance Scam