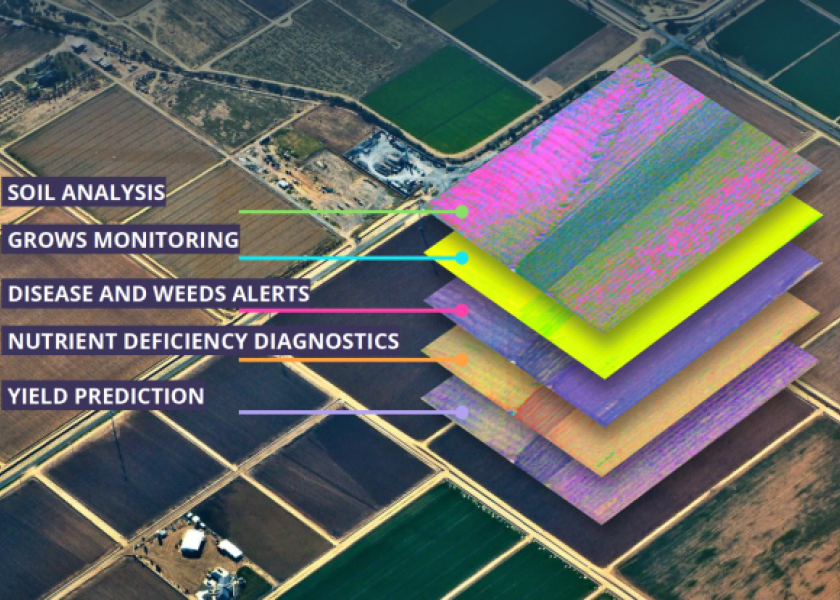

Learn More About a Crop with Hyperspectral Images

Agtech startup company Gamaya highly depends on drones for its technology. But according to the company's CCO, Igor Ivanov, it really doesn't matter what kind of drone farmers use, as long as it can carry a 250-g payload.

That's because Gamaya is not a drone company - it deals in gathering and analyzing hyperspectral images, instead. These images are jam-packed with up to ten times the amount of information as their multispectral counterparts.

"The difference is kind of like going to the doctor and getting an MRI scan, versus just getting the basics like your temperature and heart rate taken," Ivanov says.

There have been two major hang-ups with collecting hyperspectral images, he adds. In limited military uses, hyperspectral cameras could run as high as $200,000 dollars, they were too heavy to fly on smaller drones, and they grab terabytes of data. That's not a practical combination for the civilian world.

But a European research team developed and patented a camera and analytical

software package that could compress the data at a 100x rate without losing any of the information. Suddenly, the cost and data processing time

went down dramatically, and an hour's worth of flying collected around 10 to 20 GB of data instead of 2 TB.

Now, Gamaya is flying its technology over Brazilian farms. Using machine learning, artificial intelligence and good old-fashioned boots-in-the-field for ground-truthing purposes, Ivanov and his colleagues began to train the technology to distinguish between crop and different types of weeds.

"We don't acquire one data set," Ivanov says. "We follow the crop throughout the season to build a database of spectral signatures of different weeds in different growth stages and in different intensities," he says. "The more data we collect, the more accurate the algorithms are. Once the algorithms developed, we can reliably identify and classify weeds

within

the same region without any sampling or scouting."

Hyperspectral imaging can do more than sort our weeds from legitimate crops growing in a field, Ivanov adds. Gamaya can also spot diseases, nutrient needs, crop maturity and yield estimates

based on the very specific and detailed reflected light patterns hyperspectral imaging is able to pick up.

The company spent most of its 2016 efforts in Brazil, honing its craft on the country's gargantuan fields, where up to three crops a year are grown. But in 2017, it wants to make more inroads in the U.S.

"We see a competitive advantage in the ability to detect and classify different types of

weeds," Ivanov says. "The U.S. is the biggest consumer of herbicides in the world."

The company is currently in discussions with Wilbur-Ellis agronomists how to fine-tune the technology for the U.S. market.

"We just leverage existing local agronomic

knowledge and apply it in a much more continuous, autonomous and scalable way," Ivanov says.

For more information, visit