How John Deere Turned Steel into Gold and Won Farming’s Plow Wars

When John Deere picked up a broken bandsaw blade at an Illinois mill, brushed away the sawdust, and carted home the steel in 1837, he set agricultural revolution in motion via industrial scale production of a tool for the people, the self-scouring moldboard plow.

Over 185 years later, in February 2023, the last moldboard plow is set to roll off Deere’s assembly line, closing the curtain on a farming icon. Ranked by the Smithsonian among the tools that made America, the impact of Deere’s plow is difficult to overstate. Simply, when Deere’s fledgling shop forged its first moldboard plow—agriculture and American history changed forever.

Plow Wars

Financially skinned and facing bankruptcy, responsible for four children and a fifth in the oven, John Deere, 32, jumped ahead of his creditors in 1836, leaving Vermont for prospects in northwest Illinois. With $73 in his pocket, he settled in Ogle County’s Grand Detour beside the Rock River and built a 26’-by-31’ blacksmith shop.

Deere tackled an age-old conundrum: build a better plow. Millennia in the past, whether along the Tigris, Euphrates, Nile, Yangtze, or Indus rivers, a plow was little more than a stout stick deployed to break open the earth, pulled by humans or livestock. The Romans added an iron plowshare, and Medieval Europe made further improvements—but a plow largely remained as frozen technology until the 1700s. By Deere’s day (born 1804), during the constant creep westward across virgin ground of the United States, the race was on to craft a plow with unprecedented efficiency. It was the age of plow wars.

In 1797, New Jersey’s Charles Newbold received the first U.S. patent for a cast-iron plow. Ten years later, David Peacock (also from New Jersey), gained a patent for an iron plow. (Newbold promptly sued and won $1,500.) In 1819, Jethro Wood (New York) was awarded a patent for a plow with interchangeable parts.

Despite considerable plow innovations during the era, patent infringement was a major liability for any inventor, particularly in the isolated fields of agriculture, and no one knew the patent pitfalls better than a New England innovator who immediately preceded Deere on agriculture’s timeline—the forever frustrated Eli Whitney and his “worthless” cotton gin.

Nightmare of Invention

Less than 50 years prior to Deere’s plow innovation, Whitney sparked monumental agricultural change with a cotton gin invention, yet never gained riches from the technology. Prior to 1793, a lone person might pull 1 lb. of cotton lint free from its seed in a day; but Whitney’s gin separated almost 50 lb. of cotton in the same period.

However, Whitney experienced the ultimate nightmare of invention: a meaningless patent due to the simplicity of his invention. The U.S. patent office was in its infancy, and Whitney served as a proverbial guinea pig. For farmers or entrepreneurs with mechanical know-how, Whitney’s patent was a bother—a trifle to be ignored. With no legal roadblock, gins were hammered out and cotton fiber hauled in: “Thanks, Eli. There’s the door; don’t bump your head leaving.”

Jumping into legal purgatory, Whitney became entangled in lawsuits that drained his finances. He received validation of the gin patent in 1807, but the profit window was already shuttered and the money brought in only countered losses after 14 years of litigation.

Helpless, Whitney watched as cotton became commerce, his claims growing fainter all the while. The despair in Whitney’s writing still stings: “Some inventions are so invaluable as to be worthless to its inventor.”

Thirty years later, Deere’s plow success would be the inverse of Whitney’s gin debacle.

Open Door

Credit for the first steel plow may belong to farming’s forgotten man: John Lane. Mirroring Deere, Lane was a transplant Illinois blacksmith in Home Township, a present-day suburb of Chicago.

Lane, as did all blacksmith plow makers, sought a solution to the drag of cast iron and sticky prairie soils of the Midwest that often clung to the blade, requiring a farmer to make consistent cleaning stops. The answer? Sleek, polished steel.

Foreshadowing Deere, Lane obtained a steel sawmill blade and cut away three pieces, welding two to the moldboard and one to the share of an iron plow. Without a patent, he began crafting steel plows—but only at numbers according to individual demand. Lane’s plow creation was a genuine technological success, but he did not churn out plows for the masses.

Translated: The door was left wide open for a massive entrepreneurial push. Four years later and roughly 100 miles west of Lane’s shop, John Deere was about to win the plow war and make history.

Insatiable Demand

At peak, several thousand U.S. companies churned out plows. Distribution was typically regional, with each small business vying for the attention of local farmers. In 1837, echoing Lane’s technological advance, Deere turned a steel sawmill blade into gold by manufacturing and marketing the self-scouring, steel moldboard plow. (In 1864, Deere obtained his first moldboard-related patent.)

Initially sold for approximately $10-$12 apiece, the rapidity of Deere’s moldboard plow success is a stunning study in numbers. In 1837, Deere produced a single steel moldboard plow. In 1838, he bumped output to two plows. 1839; 10. 1840; 40. 1841; 75. 1842; 100. 1843; 400.

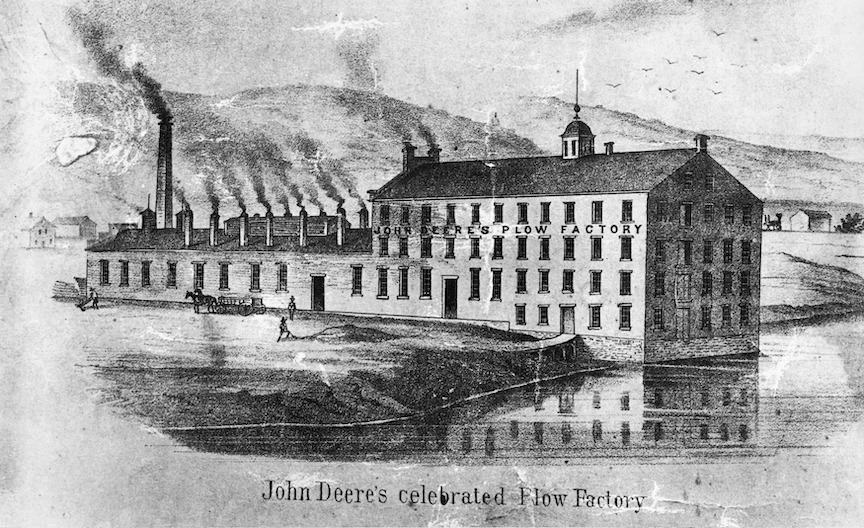

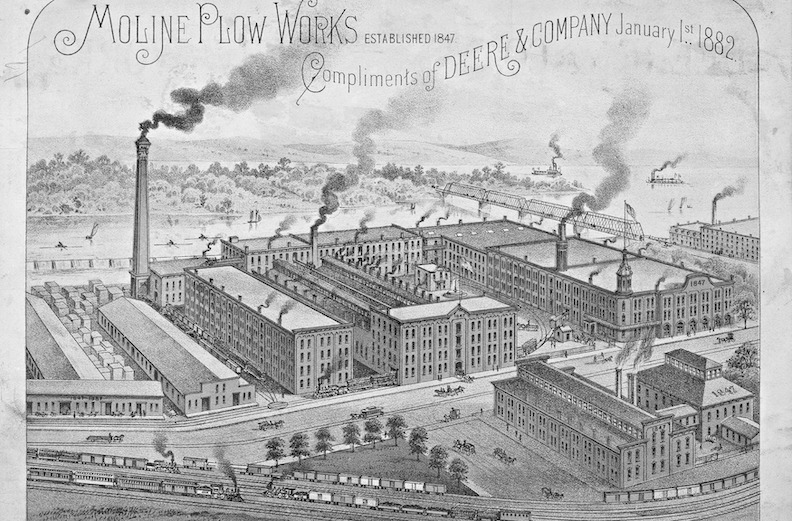

Significantly, when the railroad bypassed Grand Detour in 1843, the prescient Deere read the tea leaves and pulled stakes. He moved his operation to Moline on the Mississippi. By 1848, and construction of a new production facility, Deere pumped out 700 plows. Yet, as settlers spilled west and cut out more farmland, the demand for plows was insatiable.

In 1857, Deere made 10,000 plows. By 1859—15,000 plows. Behind the moldboard’s initial mass-production advance, in conjunction with the marketing genius of his son, Charles, Deere’s name became synonymous with farming and his machinery empire eventually covered the globe. (Deere died in 1882; Charles followed in 1907)

According to USDA, over 100 years after Deere’s first moldboard, peak plow production for all companies “occurred in the 1950s and 1960s when 75,000 to 140,000 units were shipped annually (USDA, 1965, 1977; Reicosky and Allmaras, 2003). In the late 1980s to 1990, fewer than 3,000 moldboard plows were shipped annually in the U.S., and the number of moldboard plows shipped by manufacturers dropped from 46,300 in 1977 to 1,400 in 1991 (USDC, 1992).

The Plow Whisperer

In Trempealeau County, Wisconsin, 50 miles north of Lacrosse, lives a plow enthusiast and plow historian with no peers. Raised on a Wisconsin dairy farm, David Wolfe, 67, began plowing at age 8 with a John Deere A tractor and a 2-bottom unit. He was hooked for life. Wolfe’s obsession led to authorship of three books—Plows and Plowing, The John Deere Moldboard Tractor Plow, and The John Deere Moldboard & Disk Plow. In addition, Wolfe amassed a historic collection of 100-plus unique plows (recently auctioned), ranging from the 1800s to the 1960s.

Deere’s plow success, Wolfe contends, derives from several key sources. “First, Deere was a blacksmith with his eye on making money in the long-term—way beyond his little shop. Second, he knew steel like few guys did in that day. Third, his son, Charles, was a true genius marketer and the main spoke in the wheel to take the Deere name nationwide.”

The competition, Wolfe explains, was brutal. “All land west of the Mississippi was getting settled and everyone needed a plow. The market was so strong that guys rushed into the business and there were too many plow companies to count. Basically, John Deere got in front of the crowd and made sure the public could purchase his plow. It became a springboard for almost every other kind of farm machine or tool.”

“The Syracuse Chilled Plow Co. sold more than 100,000 plows in 1910. In 1911, Deere & Co. purchased this Syracuse, N.Y. plow company, and obtained a fair share in the Eastern plow market,” Wolfe continues. “At this point I believe this made Deere & Co. the largest plow company in the world, for a while.”

Where does Wolfe rank Deere’s moldboard innovation? “It’s got to go in the top five of any list. If John Deere came back today and saw modern agriculture, he would know it all ties back to the moldboard plow. It’s not an exaggeration at all to call what developed from the steel moldboard as one of the most astonishing technological achievements in history.”

Last of the Breed

In February 2023, the last John Deere moldboard plow—a 6-bottom with coulters, listed at $67,000—will come off the factory line. It marks the end of a stunning Deere chapter as tillage capabilities evolved and farmer needs changed.

From the starting gun of 1837, how many moldboard plows did Deere make? Neil Dahlstrom, branded properties and heritage manager for John Deere, says the answer is open to speculation. “I don’t have any way to estimate this unfortunately. There were some numbers in the 1940s, which is the last estimate I’ve seen, and I don’t have any resources that would facilitate even calculating a figure.”

Deere’s original 1837 self-scouring moldboard plow is lost to time, but the second is preserved. “The second John Deere plow, dated 1838, still exists,” Dahlstrom says. “It is on exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington D.C. and was donated to the Smithsonian by John Deere in 1938.”

Respect to an American titan and his self-scouring moldboard plow innovation—steel that shaped history.

To read more stories from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com 662-592-1106) see:

Young Farmer uses YouTube and Video Games to Buy $1.8M Land

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.

Bagging the Tomato King: The Insane Hunt for Agriculture’s Wildest Con Man

While America Slept, China Stole the Farm

Bizarre Mystery of Mummified Coon Dog Solved After 40 Years

The Arrowhead whisperer: Stunning Indian Artifact Collection Found on Farmland

Where's the Beef: Con Artist Turns Texas Cattle Industry Into $100M Playground

Fleecing the Farm: How a Fake Crop Fueled a Bizarre $25 Million Ag Scam

Skeleton In the Walls: Mysterious Arkansas Farmhouse Hides Civil War History

US Farming Loses the King of Combines

Ghost in the House: A Forgotten American Farming Tragedy

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Evil Grain: The Wild Tale of History’s Biggest Crop Insurance Scam