Got Chicken Litter? Pot of Soil Health in Poultry Waste

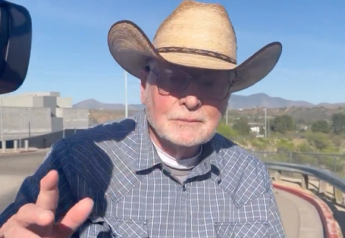

Mike McGregor rumbles down the turnrow of a buckshot soybean field and pulls a long train of dust behind his truck as he checks up behind a blue fertilizer buggy filled with chicken litter. He turns the buggy’s regulator wheel to control the gate’s spread rate and is back in his truck within seconds, seamlessly barking out direction to his operators over a CB radio. McGregor, agriculture’s version of the consummate field general, commands his chicken litter operation with military precision – and the results are evident in the flatlands of the southeast Arkansas Delta.

Hauling and spreading 2,000 loads of chicken litter each year in the Delta is a logistical nightmare. Equipment, supply, weather, downtime and producer whims – all the pieces play at different tempos, forcing McGregor to strain unity from complexity. “I’m an outdoors person and I love agriculture. People have always laughed at me for fooling with stinky chicken litter, but they don’t recognize a road to soil health. Chicken litter is far more than NPK. It’s the NPK plus all the micronutrients that deliver bang for buck. Growers that have used litter for years don’t continue because it doesn’t pay; they’re still putting it on because it brings results.”

In 1991, McGregor bought a small cattle farm on hill ground in Coleman, Ark., and began shipping hay nationwide – attempting to pump out the best Bermuda grass yields his land would allow. Yet, the ground was poor, sucked dry of nutrients by continuous cotton dating back before the steamroll of the boll weevil. Ever the perfectionist, he considered the advice of a chicken producer that was getting high tomato yields with 8 tons of litter per acre. McGregor bit the financial bullet and put out 2 to 3 tons per acre across his Bermuda grass, and began noting a major boost in phosphate, potash and pH. “We were harvesting 125 65-lb. bales of Bermuda grass four to five times a year – ridiculous numbers. That’s what keyed me in to chicken litter.”

When McGregor addresses the economics of agriculture and chicken litter, he carries a uniquely qualified perspective – nine years as a professor of finance and investment at the University of Arkansas-Monticello. In the early 1990s, McGregor began helping producer Matt Miles, McGehee, Ark., crunch numbers for his cotton module hauling operation and general farm business decisions. In 1995, Miles noticed the results on McGregor’s Bermuda grass and asked if litter success would translate to row crops. Miles had just taken on Dickens Farm in Jerome, Ark., for Ted Glaub, primary owner, Glaub Farm Management, and wanted to improve nutrient-poor land. “Matt and I hit about 200 acres at 2 tons per acre. At first it was experimental and we were trying for our own version of variable rate. On poor field spots, we’d drop a gear from 8 mph to 6 mph. Matt was confident in my mathematics, finance and perfectionism. We didn’t know exactly where we were going, but we knew we’d get there,” McGregor remembers.

For more on Miles, see Breaking Through Farming’s Veil of Secrecy

Miles began requesting more litter for expanded acreage. Initially, Miles wanted litter solely for corn, but quickly added cotton and soybeans. “One day, Matt says, ‘I want you to put chicken litter on every acre I work.’ Are you kidding me? In addition, Ted Glaub said he wanted 2 tons per acre on everything for three consecutive years.”

McGregor’s litter operation went from 25 loads to 200 loads the second year and 500 loads the third year. Miles’ yields on the Dickens ground began picking up dramatically. With that jump, neighboring farmers began demanding litter from McGregor. He was stockpiling litter on turnrows and hauling in the spring and fall. “Matt was saying he wanted 1.5 tons on 6,000 acres per year – 9,000 tons. His neighboring farmers were asking for more litter.” McGregor kept possession of his growing cattle farm -- Organic Solutions Farms, Inc. – now 1,000 acres, but walked away from his teaching position and ownership of an Electrolux franchise with three stores. Chicken litter as a part-time job was finished.

|

On average, Mike McGregor’s crew spreads litter on 750 acres per day with four John Deere tractors, four Adams fertilizer buggies, and a single Caterpillar loader. © Chris Benentt |

Dickens Farm is a textbook case of litter success, according to Glaub, who manages farms for absentee owners and also is involved with consulting and auctions. When Miles began working the ground, fertility was extremely poor – plant consumption had consistently exceeded application. “We went with litter as a cheaper nutrient source and have applied it for 10 years,” Glaub details. “Mike provides a high-quality and consistent chicken litter product. In addition, he applies it timely and uniformly. Before Matt Miles got involved with the land and chicken litter, we were hitting 35-bu.-soybeans, but that ground averaged 80-bu. soybeans last year.”

Glaub uses litter on corn, cotton, soybeans, rice and wheat, but warns it’s not a cure-all with a one-time application. “I’m constantly driving farm roads and I see a significant amount of increase in chicken litter use, but you’d be cheating yourself to expect instant results. It’s a system where the entire team of farmers, managers, crop consultants, and Mike McGregor are involved. We’re trying to be holistic and not just mine the land. We want to make it better for future generations and use natural products when possible.”

Beyond boosting fertility, litter improves soil properties through the addition of organic matter that helps with water and nutrient holding capacity, says Larry Oldham, Extension soils specialist, Mississippi State University. “Chicken litter is an excellent fertilizer and provides all the NPK macronutrients, secondary nutrients -- calcium, magnesium, sulphur -- and micronutrients.”

On average, McGregor’s crew spreads litter on 750 acres per day with four John Deere tractors, four Adams fertilizer buggies, and a single Caterpillar loader. Premium quality litter is the mantra for McGregor and he pulls samples from each chicken house for analysis. In May through August, he drops hen and broiler litter that’s gone through five or six flocks on turnrows for fall application, and spreads the loads from September to November. Logistically, there is no way to haul litter in the fall; it has to be ready and waiting on the turnrow. “In order to have quality litter, I have to order from a chicken producer a year in advance. If a grower waffles, I’ve got to let him go because I’ve got to honor my word to the chicken producer. I’ve seen farmers nervous because they can save a few bucks by not using chicken litter. However, the big majority don’t bat an eye because they’re watching the results build in crop productivity,” McGregor notes.

|

Chicken litter provides the parts for a healthy soil equation, but litter loads aren’t necessarily equal and a range of variability can be found. © Chris Benentt |

Although chicken litter provides the parts for a healthy soil equation, litter loads aren’t necessarily equal and a range of variability can be found. The quality of litter is a key issue and McGregor’s operation is associated with a reputation for premium product. He makes certain his farmer clients get a minimum of five or six flocks on every delivered load. “My No. 1 goal is to make farmers satisfied and give them the best chicken litter product I possibly can offer – application and spread. It’s a privilege to be allowed to work on my customers’ farmland. If I do my job right in serving farmers, they get better economic results than if they had spent the same amount of money on commercial products.”

As a field general across thousands of farm acres in the Arkansas Delta, McGregor has developed a thriving fertility program – feeding the soil through his chicken litter system, but keeps close tabs on success with a humble perspective. “Family, employees, and particularly me – we all know our success comes through blessings from the good Lord. I love my job every day because I make a lot of farmers happy.”